Introduction: Defining Poverty

Every single organization works towards accomplishing its vision and mission from within an implicit or explicit worldview framework. This is even more so the case when we talk about organizations, movements and institutions that seek to “develop” or “transform” the urban poor geographies in which they work. We are no exception. It starts with the way we define poverty and think about ‘success’ in transformational development. This is not simply an academic exercise, for the way we define poverty and ‘success’ – either implicitly or explicitly – says a lot about our worldview framework and view of cultural change. It also influences how we relate to the poor and plays a major role in determining the solutions we use in our attempts to alleviate poverty.1

For example, over the last four decades a growing number of Non-Governmental Organizations have advanced the concept of “poverty as lack of access to power”, due to the social and political exclusion of poor people from decision-making processes. Their solution, predictably, has focused on ‘empowerment’, community organizing, the work of social justice, advocacy and legislative change.

Numerous social and revolutionary movements of the past 60 years have advanced a similar, though slightly nuanced understanding of poverty: “poverty as systemic disenfranchisement”, the result of oppression by powerful people and vested interest groups. Consequently, they have concentrated on systemic change, using mass demonstrations, civil disobedience and, in some instances, guerilla warfare, as main tactics to achieve their goals: the redistribution of wealth and the removal of those in power.

Others, like the World Bank, for many years relied on a Western definition of “poverty as deficit, as lack of material resources”. Unsurprisingly, the concept of development was primarily identified with economic growth, infrastructure development and the restructuring of markets toward free market economies, which in turn would facilitate wealth creation. Over time, the concept of “poverty as lack of knowledge” was added and hence the term “development” was also applied to gains made in an increasing number of complementary areas of human existence, foremost education: basic primary and secondary school education, gender equity, improved agricultural techniques, vocational and business training, public health prevention, citizenship and human rights education, good governance and public policy consulting etc.

Certain Christian organizations and groups, in turn, have spread the concept of “poverty as spiritual brokenness, sin and result of demonic activity”. Their solution, consequently, has focused on evangelism, prayer and spiritual warfare.

The way we define poverty and ‘success’ – either implicitly or explicitly – says a lot about our worldview framework and view of cultural change.

Despite some advances, solving the problem of poverty continues to perplex millions of practitioners and thousands of institutions involved in the difficult task of alleviating poverty. After decades of mixed results, hence, the World Bank at the turn of the millennium decided to listen and consult “the true poverty experts, the poor themselves,” by asking more than sixty thousand poor people from sixty low-income countries the basic question: what is poverty?2 The results, published in a three-volume series of books called Voices of the Poor, sheds light into an often overseen aspect of poverty: Poverty as “shame, inferiority, powerlessness, fear, vulnerability, humiliation, hopelessness, depression, social isolation, voicelessness, and lack of opportunity and real choice”. In fact, according to Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen, it is this lack of freedom to grow and make meaningful choices – to have the external and internal ability to change one’s situation – that is the distinguishing feature of poverty. 3

Within the SHALOM Cities Initiative, we have identified five root causes of poverty and developed corresponding working definitions for urban poverty. These five core beliefs form the basis of our integrated and yet still evolving understanding of urban poverty.

Definition 1: “Urban Poverty is based in hopelessness and a web of lies that entraps the poor in an ongoing cycle of indignity.”4

Since World War II the concept of development has been largely defined and implemented without major consideration given to the influence of psycho-spiritual and worldview factors. This is unfortunate since it underestimates an important source of chronic poverty – the poverty of being.

Poverty can exist within the mind and spirit of a person and even a community. Many urban poor dwellers struggle with hopelessness, anxiety, shame and a deep sense of inferiority. Some suffer from spiritual oppression – from a crippling God-image and stifling religious beliefs, or from fear of spirits, demons and ancestors. Others drown their hopelessness in alcohol, drugs and sexual addictions, seeking to find some sense of relief in these behaviors. As a result, they lack focus and moral anchoring, and unable to believe that change is possible, they aimlessly drift through life.

A lifetime of suffering, deception and exclusion can leave deep scars and break a person’s spirit. It gives way to an internalized worldview where many believe they are of no value and have nothing significant to offer. Through pervasive advertising and television programs, they are reminded daily of the economic distance that separates them from the rich. Believing they don’t matter and can’t make a difference, they don’t even try. Instead, they bury their talents in the ground and let their spirits wither. With hopes and opportunities dimmed, some become predators joining criminal gangs and preying upon the weakest members of their communities. Others simply resign themselves to the belief that this is all there is to life, and that things will never change. This is the deepest and most devastating expression of poverty: moral, spiritual and psychological poverty – the root of fatalism.

We can empathize why many poor people succumb to a fatalistic worldview to cope with their daily struggle for survival. Nonetheless, this poverty of being arises from a web of lies inside the mind: Lies about oneself; about one’s identity, value and capacities. Lies about one’s powerlessness. Lies about the immutability of one’s current situation. Lies that this is how God ordained things or that God or the gods may be punishing them for something they did in the past. Some of these lies people tell themselves and believe about themselves disempower them, making them assume roles of perpetual victims. Others are lies that arise externally and are perpetuated and reinforced by those in power. Every culture has beliefs that disempower people, discourage change, and label oppressive relationships as sacrosanct and ordained.5 Indeed, culture is most powerful when it is perceived as self-evident. In this way, the structures of culture form the structures of consciousness and shape the implicit understandings of what is good, worthy, appropriate, right, wrong, abhorrent, and evil.6

Perhaps the most important thing to realize here is that those in power often are successful at defining the social, economic and political centers, which in turn dictate our values so as to direct our way of life. Over generations they have molded culture to such an extent that its narratives, myths, symbols and lies are so deeply embedded in our consciousness, the habits of our lives, and our social practices, that they are seldom called into question.

No wonder, the same web of lies not only affects the poor, but also the non-poor. There too, many believe in the impossibility of real transformational change. While gladly accepting their better lot in life, they only look to the wellbeing of themselves and their loved ones, assuming that that’s all they can and are supposed to do. Unfortunately, by accepting the narratives, structures, and systems that justify and rationalize their privileged position as non-poor, they unwittingly help cement the foundations of poverty.

Some non-poor take this web of lies a step further by expressing the same poverty of being in the opposite way of the poor. Believing themselves to be superior, indispensable, and anointed to lead, they succumb to the temptation to play god in the lives of the poor. They use religious systems, business connections, the media, cultural stereotypes, the law, government policies, party politics and people occupying positions of power to advance their interests, often to the detriment of the poor.7 Indeed, their interests are served by sustaining the illusion that the limitations of the poor can never be changed, and so they use manipulation, exploitation, oppression, intimidation and coercive force as tools in their quest to stay in power. In due time they stop being who they truly are and end up dehumanizing themselves, as Brazilian educator Paulo Freire eloquently put it.

Transformation begins with changed people. It is a transformed person who transforms their environment.

Of course, all of these things keep the poor from seizing opportunities and moving forward, reinforcing the vicious cycle of poverty. What’s more, since trauma and pain afflict not only individuals but can affect entire regions when they become widespread and ongoing, isolation and distrust become the mark of such multiply wounded communities. This, in turn, hinders effective transformational change, but, instead, keeps people caught in a never-ending poverty cycle where all they know to do is survive, bear life and fend for themselves.

In this sense we believe that both the poor and the non-poor are caught in a web of lies that mar their true identity and vocation. Yet we cannot solely blame their condition on this web of lies. We also have to realize that the cause of poverty is fundamentally spiritual. Sin (which we could translate as distrust and relational brokenness) mars our lives, our relationships, our ability to change and our hope for the future. It incites us to make bad choices all the time. It distorts how we view our own existence and that of others around us. Marred by sin, our relationship with ourselves can assume the characteristic of either self-loathing or self-indulgence, realities that both the poor and non-poor struggle with. Our relationships with others and with the environment oftentimes are poor representations of what we wish they were. For reconciliation to take place, a new identity and vocation must be discovered in the knowledge that we bear the image of God and are infinitely valuable to him. At the heart of this kind of change is repentance and forgiveness, the twin foundations of reconciliation.8 So we hold that people will ultimately only experience sustainable change if this root cause of poverty is addressed and the poor and non-poor alike experience the empowering presence of the Holy Spirit, which will allow them to transform their minds and renew their lives.

From the SHALOM Cities Initiative point of view, we realize that it is people who cause and perpetuate poverty in important ways. It is easy to blame greed, systems, the market, corruption, and culture, but these are abstractions and cannot directly change people – the poor and the non-poor have to change. Without understating the need for systemic and structural change, transformation begins with changed people. It is a transformed person who transforms his or her environment. All other transformational frontiers are more easily breached in a more comprehensive way and with greater hope of being sustainable, when people change.9 Having said that, the subsequent definitions add important complements to this particular view of poverty.

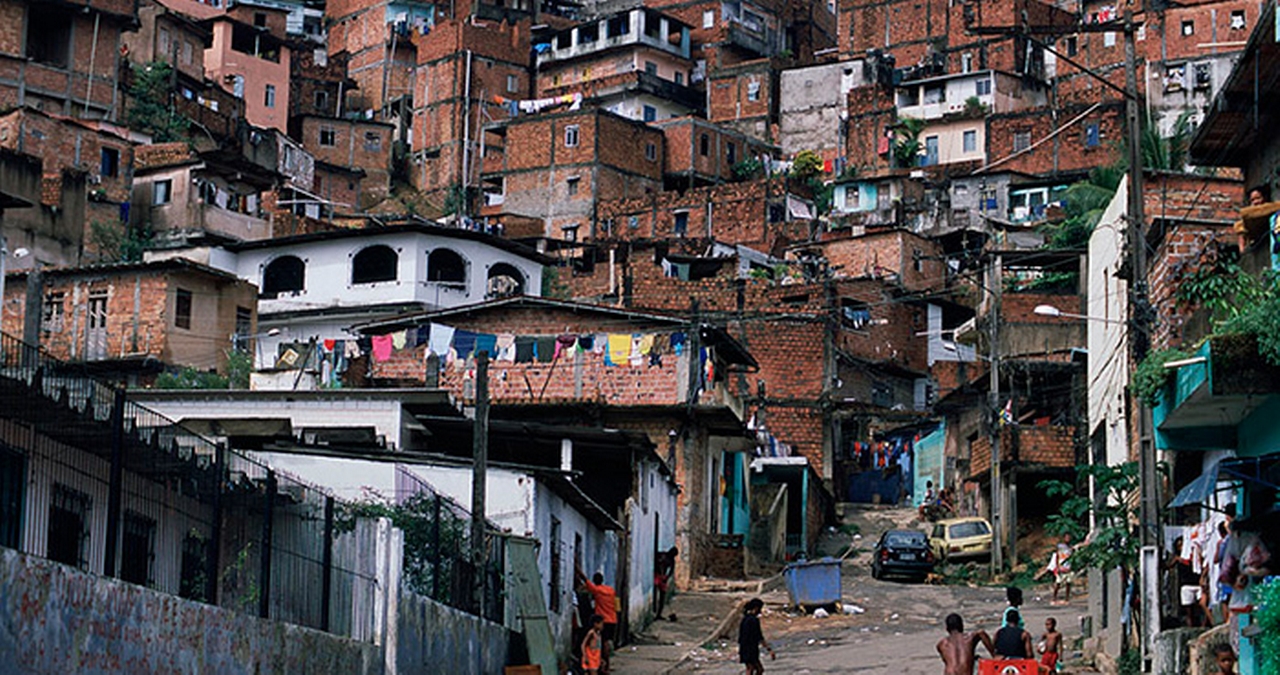

Definition 2: “Urban Poverty is multi-dimensional.”

Over the past three decades it has become accepted truth that poverty can no longer refer to material deprivation only. It is a multifaceted experience for those who are struggling to get by. The United Nations now defines poverty as follows: “Fundamentally, poverty is a denial of choices and opportunities, a violation of human dignity. It means lack of basic capacity to participate effectively in society. It means not having enough to feed and clothe a family, not having a school or clinic to go to, not having the land on which to grow one’s food or a job to earn one’s living, not having access to credit. It means insecurity, powerlessness and exclusion of individuals, households and communities. It means susceptibility to violence, and it often implies living in marginal or fragile environments, without access to clean water or sanitation.”10

Unsurprisingly, these multiple causes of poverty tend to cluster and reinforce each other, making poverty alleviation a very complex endeavor. No single intervention can alleviate poverty. Failure to recognize this has squandered billions of dollars in development aid and led to many well-intended interventions that have caused more harm than done good.

Indeed, evidence shows that results from single-issue or short-term projects are superficial and quickly dissolve. They lack synergy and do not have credibility in local populations, because these have not even been consulted. In fact, they often cement dependency and paternalism by regarding the poor as passive recipients of aid programs. What’s more, single-issue interventions sometimes exacerbate the poverty of the poor by benefitting local elites and transnational interests. The following two examples illustrate this insight.

Over the course of the last six decades hundreds of millions of farmers have been evicted from their lands by dams, logging concessions, and large scale agricultural and industrial projects, all implemented under the guise of national progress. No longer able to make a living off their lands, these subsistence farmers have become the landless poor that have flocked to the slums of cities around the globe.

The botched structural adjustment programs of the 1980s and 1990s are another case in point. Imposed on many developing nations by the World Bank, the IMF, the U.S. Treasury and other Western governments, they concentrated mostly on fixing financial markets, liberalizing trade, and improving economic growth. While these measures helped some countries improve their economic performance, believers of the so-called neoliberal Washington Consensus failed to understand the complexities of transformational change. And so, their actions, based on a flawed theory of change, resulted in deepening income inequality, increased levels of poverty in some countries and rising rates of violence, crime and city-to-city migration, with people fleeing growing urban violence and terrorism.

From the perspective of the SHALOM Cities Initiative, we understand poverty as a multidimensional phenomenon. Poor people have a range of physical, emotional, social, political, environmental and spiritual needs.

Another popular approach has been to relegate the cause of poverty exclusively to unjust systems, oppressive power structures and those who perpetuate them. The poor are viewed as the helpless victims of powerful interests, which deny them meaningful participation in society. As a result they continue to be excluded and marginalized from the nation’s progress. The primary means to revert this situation, in view of that, is to work towards the poor’s access to social power.

While this assessment needs to be taken seriously, we believe that this generally left-leaning view, is based in an unrealistic understanding of poverty and that its theory of change will fail to deliver the goods:

- One, it paints the poor exclusively as victims and negates their contribution to their own poverty. By brushing aside the need for the poor to address brokenness in their own lives and relationships, it undermines the meaningful and responsible participation of the poor in their own personal growth and development.

- Two, it believes that the primary means to poverty alleviation is embedded in a confrontational model of class warfare: organizing the poor and their sympathizers to confront those in power and getting them to acquiesce to the poor’s demands. This approach, though certainly appropriate and needed in some circumstances, promotes entrenched battle lines, tends to demonize opponents, excludes from meaningful participation those who disagree with the ideological idiosyncrasies of this particular view, and polarizes a society. Also, it often assumes that the end justifies the means, which, as history has shown, usually leads to the manipulation of the poor by the very ones who lead them in class warfare. By doing so it accentuates and adds to the poverty of the poor.

From the SHALOM Cities Initiative point of view, we understand poverty as a multi-dimensional phenomenon. Poor people have a range of physical, emotional, social, political, environmental and spiritual needs. Hence, appropriate interventions must include such diverse sectors as economic development, health, education, housing, environmental upgrading, civic and political participation, spiritual formation, cultural change etc. Only a comprehensive approach to poverty alleviation, which takes into account systemic AND personal causes of poverty, will be able to overcome it.

Thankfully, this view has taken hold among many experts. For example, the United Nations Development Program, in collaboration with the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, created the Multi-dimensional Poverty Index in 2010 and rolled out a new version in 2018, reaffirming the need for multi-dimensional approaches to poverty eradication.

Definition 3: “Urban Poverty, in essence, is a breakdown of relationships.”

Definitions of poverty often overlook the relational dimension of poverty. Poverty, in essence, is the result of relationships that do not work, that are not just, that are not for life, that are not harmonious or enjoyable.11 Why are the poor denied access to social power? Why do economic policies often benefit the rich over the poor? Why are there constraints to growth? Why is there widespread violence – whether by organized crime or by family members? Why do many people live in insecurity and fear? What is at the root of the disempowerment that results?

The answer is simple: Deceptive, dominating, indifferent and broken relationships. We can clearly observe how broken relationships affect the relational dynamics among the poor, and the relational dynamics between the poor and non-poor.

While the following is not true for all urban poor communities and all urban poor dwellers, the relationships of the poor often don’t work for the well-being of the poor. Many households suffer from broken and dysfunctional relationships with each other, frequently resulting in verbal, physical and sexual violence. Children growing up in such circumstances typically reproduce their learned abusive behaviors in other social contexts. Some urban poor dwellers, having internalized the societal dynamics of oppression, exploitation and deception, turn on each other, oppressing, exploiting and deceiving the most vulnerable members of their community.

In fact, the much-famed solidarity among the poor is absent in many urban poor communities. Given the heterogeneity of urban poor populations, more often than not distrust, fear, envy and gossip characterize relational dynamics between neighbors. As a consequence, communities are divided and don’t work together to address needs and issues that affect all and that can only be resolved by the community working together. Instead, those who try to bring about change often find themselves alone and become discouraged by the inaction, apathy, suspicion and criticism of the rest. Finally, they too resign themselves to the way things are. It follows that broken relationships breed isolation. And so, much-needed social capital in the form of social trust, friendship and community is seldom found in urban poor settlements.

Healing the divide and fostering social cooperation among the poor and between the poor and non-poor is critical to significant long-term change.

In a similar vein, the relational dynamics between the poor and non-poor are exacerbated by the fact that, even though they often share a common language, culture and place, the poor have become “other” to the non-poor and vice versa. Even while the poor know about the rich and the rich know about the poor as statistical entities, they hardly ever know each other. Instead, the poor fear, envy, despise or, in some cases, objectify the rich as patrons and potential redeemers that will help them escape poverty, if only temporarily. Entire societies have been built on variations of this patron-client model.

Some rich, in turn, fear the urban poor masses and seek to protect their wealth and families behind gated communities and exclusive country clubs. Others unabashedly use their power to intimidate, deceive, coerce, exploit and rob the poor who can’t do anything to defend themselves, even if they wanted to. Yet others, support relief efforts among the poor, but do so out of a desire to be seen as benevolent philanthropists or even mini-saviors. By not forfeiting their god-complexes they continue to disempower and objectify those they say they want to help. In fact, these elites essentially use the rhetoric of changing the world to prevent change. By trying to persuade people that philanthropy is the answer to inequality, they dodge the structural changes that would re-establish the social contract and create a more level playing field.12

Many middle-class citizens simply avoid taking responsibility, apart from the occasional charitable donation, and continue to rationalize their privileged position in relationship to the poor, by pointing to their hard work, professional success and business savvy. As a consequence, the brokenness in these relationships is expressed not just at the personal level but also via the economic, political, social, cultural and religious systems that humans create.13

Finally, a key reason for the slow progress in poverty alleviation is the inadequate participation of poor people in the process of poverty eradication. Meaningful inclusion of poor people in the selection, design, implementation, and evaluation of an intervention increases the likelihood of that intervention’s success.14 However, because many social advocates, policy makers and development practitioners have neglected the importance of building trusting and mutually embracing relationships with poor people, including them to participate in all aspects of an intervention, many development efforts have failed.

From the SHALOM Cities Initiative point of view, we recognize the profound relational dimension of poverty. Because of relationships that don’t work, that aren’t just and life-enhancing, people either become victims of oppression, or assume god-like authority in the lives of others. The work of community building, reconciliation and peace-making therefore is crucial to the transformational agenda. Healing the divide and fostering social cooperation among the poor and between the poor and non-poor is critical to significant long-term change. Without it, poverty will not be overcome.

Definition 4: “Urban Poverty exists because of unjust systems that don’t work for the poor.”

Most of the systems in which the poor live are outside of their control. So transforming the worldview, psycho-spiritual condition, emotional health and educational attainments of the materially poor will not automatically transform these systems.15 In fact, the vast majority of the economic, social, religious, cultural and political systems in which a particular individual lives are not created or even influenced by the individual. Rather, most of these systems are the result of hundreds of years of human activity operating under local, national, and international auspices. While the systems have been and continue to be shaped by human beings, most individuals, particularly the materially poor, have very little control over them. Nevertheless, these systems can play a huge role and significantly contribute to their material poverty.16

Growing inequality, for example, is not simply a personal issue, but a structural one. Extreme wealth and extreme poverty have seen a sharp simultaneous increase over the past decade. While the world’s billionaires grow wealthier, the wealth is not trickling down. “The richest 1% own almost half of the world’s wealth, while the poorest half of the world own just 0.75%. In fact, they have acquired nearly twice as much wealth in new money as the bottom 99% of the world’s population. Today, 81 billionaires have more wealth than 50% of the world combined.”17 And the five richest men in the world have more than doubled their fortunes since 2020, while the poorest 60% of the global population—nearly 5 billion people—have lost money.18

Poverty, then, is not simply a problem of attitude; it is not something people voluntarily impose on themselves for want of effort. The powerlessness of the poor is the result of systematic social, mediatic, economic, political, bureaucratic, cultural and religious processes and systems that disempower the poor.19 It is constructed by disempowering cultural beliefs and worldview frameworks, divisive and discriminatory laws, inadequate land rights, inflexible organizations, weak rule of law, corrupt political structures and acquisitive ideologies of wealth, a deeply-rooted class system, and global economic policies which serve privilege in the short term and destroy societies in the long term.20

A few examples:

On a global level, the debt acquired during the last 40 years by governing elites in developing nations via loans for development, has forced many to reduce domestic expenditure and to compete for shrinking export markets, in order to earn foreign exchange to repay this debt. In fact, “the poorest countries are spending 4 times more repaying debts (often to wealthy private lenders) than on health care.”21 Forced by dominant countries, multilateral institutions, and private lenders, they have had to choose between the approval of foreign debt collectors and credit agencies on the one hand, and their own people on the other hand. In many countries the impact of these policies on the poor has been devastating. They have implied a drop in wages and a slashing of education and health services, effectively cutting investment into the long-term development of the poor. No wonder, with little investment in education and health, countries continue to produce low-skilled laborers, who are always a paycheck or an illness away from economic disaster.

On a national or municipal level the following structural issues consistently keep the poor from progressing: inefficient public institutions, bureaucratic corruption, lack of transparency, inadequate land rights provisions, a political framework that manipulates or hinders the participation of the poor in the political process, the inability of the poor to exercise their civil rights, an economic system that intensifies income inequality, inadequate social services (like education, health, infrastructure, clean environment and benefits for women and children), and regressive tax policies (like value-added taxes) that are biased in favor of the wealthy. All of these cause enduring poverty and contribute to growing urban violence and crime, because broken systems and a weak rule of law strain the social contract do serious damage to people.

In fact, violence in many countries is spurred when states and sub-national governments do not provide security and access to justice, markets do not provide employment opportunities, and communities have lost the social cohesion that contains conflict. According to the World Bank, countries where government effectiveness, rule of law, and control of corruption are weak have a 30 to 45 percent higher risk of civil war, and significantly higher risk of extreme criminal violence, both of which contribute to chronic poverty. In surveys of areas affected by violence, citizens cite unemployment as the main motivation for recruitment into both gangs and rebel movements — with corruption, injustice and exclusion the main drivers of violence. Where violence flourishes and citizens are excluded from social justice and participation in the formal economic system, then, poverty endures and deepens.22

From the SHALOM Cities Initiative point of view, we recognize that while working in an impoverished urban community through grassroots development will directly affect urban poor dwellers opportunities to advance, as long as government policy lags social development growth, and economic systems do not create opportunities for progress, poverty cannot be reduced significantly. Transformational change needs to be both bottom-up and top-down, all at the same time.

Definition 5: “Urban Poverty persists because interventions aren’t designed for reproducibility and scalability and therefore remain small.”

Generally, there have been two approaches to poverty alleviation and transformational change: The first consists in a “grassroots approach”. Local people and/or outside social actors become convinced that something needs to be done about a particular set of needs in a specific geographic area. As a result, they roll up their sleeves and start doing something to address that need. Because of the grassroots nature of their work they are often in direct contact with beneficiaries. While first engaging in well-intentioned, but not very effective activities, over time the interventions of the most successful of these grassroots organizations become more sophisticated and technically adept. This is mostly due to the professional and experiential growth of their staff and to the fact that they intentionally seek to foster a participatory learning and asset-based approach to development. They include beneficiaries in all aspects of the transformational agenda: proposing the best course of action, implementing the chosen strategy, resourcing it with local means where possible, evaluating how well things are working, and determining the appropriate modifications. Naturally, the poor become enthusiastic and gain a sense of ownership of the transformational agenda and, as a result, they are more likely to sacrifice to make things work well and to sustain them over the long haul.23

The second approach to poverty alleviation has commonly been termed the “blueprint approach”. Usually a project is proposed, based on the findings of demographic, economic, sociological, gender or political research studies directed by professional researchers. These studies generally focus on the deficiencies and needs in communities. Once a project proposal has been accepted, the project is then designed in the offices of a government or non-governmental entity by a professional class of policy makers, economic advisers, development practitioners and social advocates. Although best practice approaches are included into the project design, the project is finally done to the economically poor. The ultimate goal of the blueprint approach is often to develop a standardized product and then to roll out that product on a massive scale in order to multitudes of people. Interestingly, the majority of post-World War II approaches to poverty alleviation have been implemented in this non-participatory fashion.

The problem with the blueprint approach is that in most cases the poor are effectively excluded from any meaningful participation in the election, design and implementation of the project and the focus is on local needs versus assets. Community residents are only consulted during post-project evaluations which are conducted by external consultants. Unsurprisingly, this approach often fails for two main reasons: It doesn’t allow poor people to take ownership of their own development process and it imposes solutions on poor communities that are inconsistent with the local culture, that are not embraced and owned by the community members, or that cannot work in that particular setting.24 Critics call it McDevelopment, the fast food franchise approach to poverty alleviation, and they claim it has resulted in more than 3.5 billion poor people not being well served.25

Many grassroots initiatives never scale their efforts to impact a critical mass of people, and when replicated in other regions and social contexts, they often seem to start from scratch.

While the SHALOM Cities Initiative finds its primary home in the grassroots approach, recognizing the drawbacks of the blueprint approach, we have also identified a problematic blind spot in the grassroots approach. In a reactionary pendulum swing against the blueprint approach, some proponents of the grassroots approach are effectively reducing their chances to alleviate poverty on a large scale by excessively emphasizing quality over quantity. It is interesting to note, that many grassroots initiatives never scale their efforts to impact a critical mass of people, and when they do reproduce themselves in other regions and social contexts, they oftentimes seem to begin from scratch. While for some this is simply due to of a lack of organization and setting priorities, others, in fact, believe that reproducibility and scalability are impossible to achieve, given the variety of cultural, religious and socio-political contexts. Being development doctrinaires, they deride the very thought of including outside ideas and interventions as an imposition on a local development process. Unfortunately, they tend to forget that they themselves are product of many outside influences and that true quality always produces quantity (fruit).

We agree with the blueprint critics that a cookie-cutter approach to development is problematic and destined to fail. Yet we respectfully disagree with development and missional purists who uphold the belief that all community transformation models must be sensitively contextualized and birthed anew in each community. We think this belief is self-limiting and does a disservice to the poor in light of the challenge of fragile cities. The fact that some approaches and methodologies that work well in Mexico City will not work well in the cultural, religious, economic, and institutional context of urban Ecuador, simply does not mean that all approaches and methodologies will fail to be transferable. In fact, we believe there is more commonality between urban poor communities in cities around the globe than commonly accepted by development and missional purists. We don’t always have to reinvent the wheel and may actually spur transformational change by incorporating best case practices into our own approaches.

In conclusion, from the SHALOM Cities Initiative point of view, we are committed to joining with development specialists and professional researchers to document and systematize promising practices so they can be reproduced and scaled in adapted and contextualized versions in new urban poor settings. We consider that failing to do so, will effectively hinder the chances of urban poverty eradication and transformational change of whole urban poor areas, limiting our impact to individuals and small pockets of urban poor dwellers. That is why we want to encourage our partner organization to seek to design most of their interventions to become reproducible and scalable.

Footnotes

- Steve Corbett, y Brian Fikkert. When Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty Without Hurting the Poor… and Yourself. Chicago: Moody Publishers, 2009: 54. ↩︎

- Citado en Ibid., 51. The three-volume work Voices of the Poor can be accessed at:

Volume 1: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTPOVERTY/Resources/335642-1124115102975/1555199-1124115187705/vol1.pdf,

Volume 2: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTPOVERTY/Resources/335642-1124115102975/1555199-1124115201387/cry.pdf,

and Volume 3: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTPOVERTY/Resources/335642-1124115102975/1555199-1124115210798/lantoc.pdf ↩︎ - Amartya Sen, Development as Freedom. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999. ↩︎

- Major tenets of this definition have been developed by the Indian theologian and development practitioner Jayakumar Christian, advanced in his book God of the Empty-Handed: Poverty, Power, and the Kingdom of God. Monrovia, CA: MARC, 1999. ↩︎

- Bryant L. Myers, Walking with the Poor: Principles and Practices of Transformational Development. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1999. ↩︎

- James Davison Hunter, To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010: 211. ↩︎

- Myers, Walking with the Poor, 73. ↩︎

- Ibid., 133. ↩︎

- Ibid., 116-117. ↩︎

- “Poverty,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poverty (accessed June 4, 2011). ↩︎

- Corbett & Fikkert, When Helping Hurts, 62. ↩︎

- “Billionaires in Davos Dodging the One Thing to Solve Inequality.” HuffPost, February 9, 2019. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/billionaires-davos-taxes-inequality_us_5c519dd3e4b00906b26f4e6c ↩︎

- Corbett & Fikkert, When Helping Hurts, 76. ↩︎

- Ibid., 142 ↩︎

- “World’s Five Richest Men Double Their Money as Poorest Get Poorer.” The Guardian, January 15, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2024/jan/15/worlds-five- richest-men-double-their-money-as-poorest-get-poorer ↩︎

- Though worldviews affect systems and systems, in turn, affect worldviews. ↩︎

- Corbett & Fikkert, When Helping Hurts, 90. ↩︎

- “Wealth Inequality: The Richest 1% Have Almost Twice as Much Wealth as 7 Billion People.” Global Citizen. Accessed January 28, 2023. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/wealth-inequality-oxfam-billionaires-elon-musk/ ↩︎

- Myers, Walking with the Poor. ↩︎

- Peter Townsend, Poverty in the United Kingdom: A Survey of Household Resources and Standards of Living. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979. ↩︎

- Accessed on January 28, 2023 at https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/wealth-inequality-oxfam-billionaires-elon-musk/ ↩︎

- World Development Report 2011: Conflict, Security and Development. Washington, DC: World Bank. Accessed June 4, 2011 http://wdr2011.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/ENGLISH_WDR%202011_SYNOPSIS%20no%20embargo.pdf ↩︎

Image Directory

- “Poverty-Lisboa-Portugal”, Victor, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0

- “Poverty 029”, Dominio Público

- “National Park Service Eviction of Homeless Tents Encampments, Washington DC”, Elvert Barnes, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0

- “Medellín´s Poverty”, Ricardo Austrauskas, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0

- “Humanitarian Aid in Congo”, Julien Harneis, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0