Abstract

This article offers a profound theological and missional reflection on the urgent need to radically redefine the concept and practice of the church (ekklesia) within the Latin American context. In a region that is simultaneously the most urbanized and most violent in the world—and where half the population is under the age of 25—traditional ecclesial models have proven largely ineffective in addressing the systemic challenges of poverty, inequality, forced migration, and structural violence. Despite the numerical growth of Evangelical Christianity, many churches have embraced paradigms centered on spectacle, religious consumerism, rigid institutionalism, and escapist theology, resulting in communities disconnected from their contexts and with little transformative impact. In contrast, the article proposes a recovery of the original meaning of ekklesia as a sent community, empowered by the Spirit and oriented toward embodying the Kingdom of God in all spheres of life. Through a rigorous analysis of Scripture, the historical context of the New Testament, and the witness of the early church, it presents four essential dimensions of the ekklesia: a healing and missional community, a Spirit-led discipling movement, a transformative force that confronts structures of death, and a worshiping community in deep communion with God. The article also traces how linguistic and ecclesiological evolution—from ekklesia to kuriakē and eventually “church”—has contributed to a reduced and domesticated vision of church, more focused on Sunday worship than on holistic mission. In response, it calls for a return to Jesus’ vision: an active and visible ekklesia that lives worship as total surrender, forms disciples in every area of life, embodies the justice and compassion of the Kingdom, and acts as the soul of the city, promoting Shalom in contexts marked by fragmentation and despair. The article concludes with a prophetic exhortation to leaders, churches, and communities across Latin America to abandon institutional self-preservation and courageously embrace their public, communal, and transformative vocation. The future of the church will not be defined by its events or the scale of its structures, but by its ability to form discipling communities, deeply connected with God and actively engaged in the restoration of their cities and nations. Only then, the article asserts, will the ekklesia become the living and sent community that Jesus envisioned—a church that challenges the gates of Hades and powerfully manifests the Kingdom of God in our generation through compassion, truth, and justice.

Part 1: The Major Challenges for the Church in Latin America

Introduction: Latin America, Between Urgency and Potential

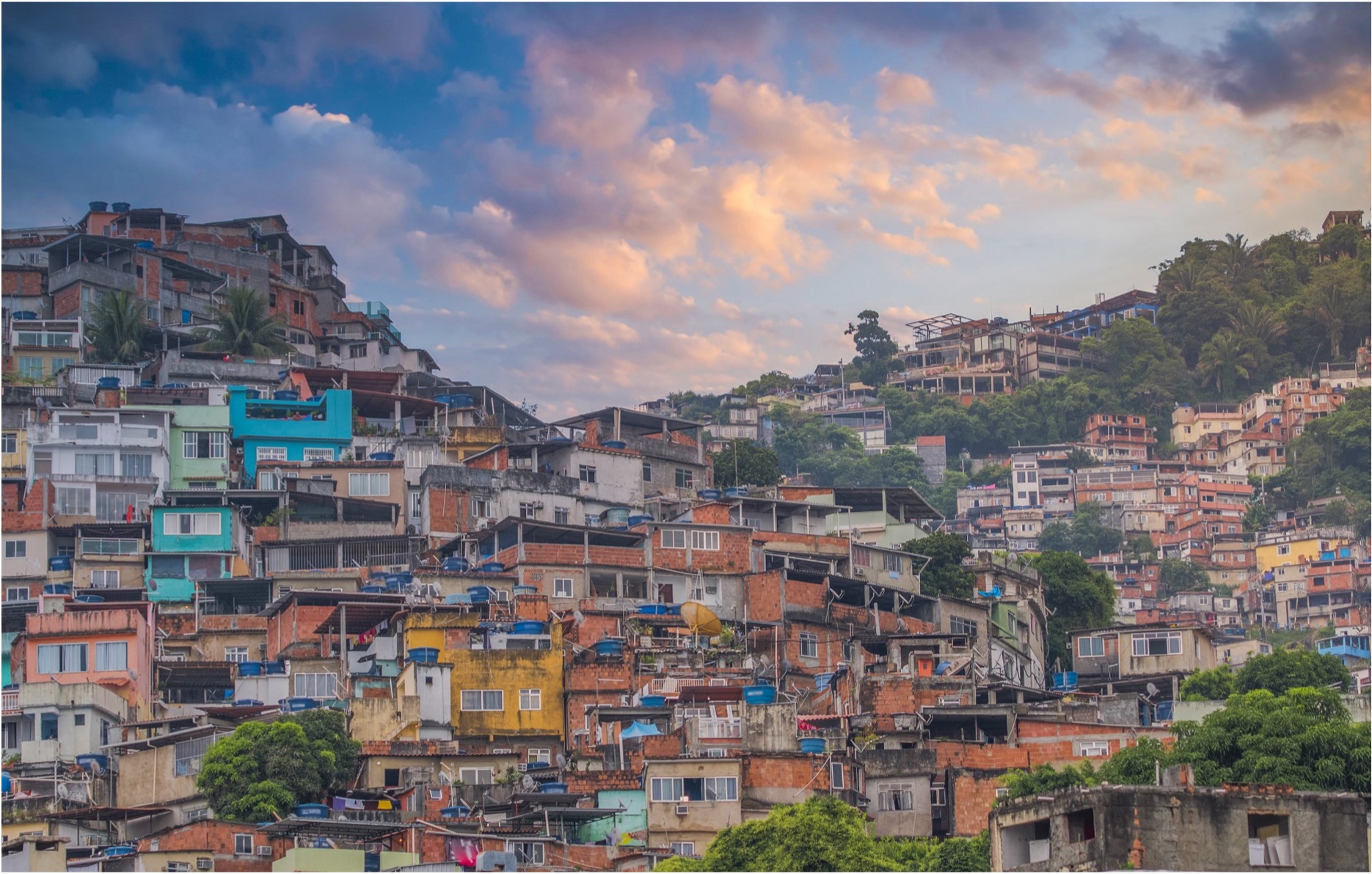

Latin America faces three fundamental and interconnected challenges—and opportunities. It is the most urbanized region in the world, with approximately 82% of its population living in cities.1 It is also the most violent, home to the highest homicide rate globally,2 and 40 of the 50 most violent cities on the planet.3 At the same time, over 40% of its population is under the age of 30, although this percentage has been gradually declining in recent decades.4 These overlapping dynamics—urban concentration, pervasive violence, and a youthful demographic profile—demand a missional response that is both contextual and forward-looking. Given that the vast majority of the population resides in urban areas, it is essential to develop church-planting models and urban ministry strategies that are tailored to the specific challenges and opportunities of city life. Likewise, focusing on the next generations is critical, as young people represent a significant portion of the population and hold the key to long-term transformation. If we are to cultivate a more hopeful and just future for Latin America, church-planting and community renewal movements must intentionally invest in the growth, formation, and active participation of youth.

More Churches, More Impact?

Tim Keller insightfully observed that, “The vigorous, continual planting of new congregations is the single most crucial strategy for reaching a city. Nothing else — not crusades, outreach programs, para-church ministries, mega-churches, consulting, nor church renewal processes — will have the consistent impact of dynamic, extensive church planting.”5

Keller’s statement has shaped much of the global conversation on urban mission. Yet it also raises a crucial question for Latin America: Is the mere multiplication of churches truly reaching our cities and producing the transformation they need? In fact, many cities across the region are full of churches, yet often without a truly transformative impact. The question, then, is not simply how many churches we are planting, but rather:

- What kind of impact are we generating?

- What kinds of churches are we planting?

- What kinds of disciples are we making?

Simply planting more churches is not, by itself, a sufficient response to the profound challenges facing Latin America—especially if we fail to ask how these churches can meaningfully engage cities and connect with younger generations. While evangelical Christianity is currently the fastest-growing religious movement in the region—with roughly one-fifth of Latin Americans now identifying as evangelicals, up from one-tenth in 20026—this rapid growth has not yet translated into deep social transformation. Despite impressive numbers, violence, poverty, inequality, and migration remain deeply entrenched.7 In countries like Brazil and across Central America—where evangelicals are expected to surpass Roman Catholics as the majority in the coming decade—the persistence of these issues suggests that quantitative growth without qualitative transformation falls short of the gospel’s intent.

Many continue to affirm that the church, as God’s chosen community, carries a sacred responsibility to generate real, redemptive change in its context. Bill Hybels once summarized this conviction memorably: “The local church is the hope of the world”8, and “Nothing on earth has greater potential to change lives and carry out God’s work in the community than the local church. There is nothing like the local church when it’s working right. Its beauty is indescribable. Its power is breathtaking. Its potential is unlimited. No other organization on earth is like it. Nothing even comes close.”9

This vision captures the extraordinary purpose for which the Church was created—to reflect God’s Kingdom in the midst of the world’s brokenness. Yet, the painful reality is that much of the contemporary church in Latin America has struggled to live up to this calling. Countless congregations remain focused solely on what happens within their own four walls. Content with maintenance rather than mission, they often lack the imagination and courage required to embody God’s reign within the complex urban fabric of our region.

“There is nothing like the local church when it’s working right. Its beauty is indescribable. Its power is breathtaking. Its potential is unlimited.”

Bill Hybels

This disconnection has created a significant gap between love for God and love for neighbor, and a troubling misalignment between the Great Commandment and the Great Commission. In today’s Latin American church landscape, we see a concerning proliferation of distorted models of church life. The Spectacle Church, driven by sensationalism and charisma, seeks to entertain rather than transform—reducing the Christian life to emotional events and flashy experiences. The Monument Church, clinging to rigid traditionalism, turns faith into an untouchable “sacred” routine—more concerned with preserving inherited forms than with creatively and faithfully responding to present realities. Then there is the Fortress Church, marked by exclusionary fundamentalism that builds walls of doctrinal purity—pushing out those who are different, prioritizing form over substance, rules over compassion, and controversy over discipleship.

Rather than cultivating an embodied, deep, and transformative faith, these models often perpetuate structures and messages disconnected from the daily realities of people’s lives—distorting or neutralizing the church’s holistic calling to embody the good news of the Kingdom in every sphere of life.

Root Causes: Theologies and Practices That Diverge from the Church’s Original Purpose

Below are some of the deeper root issues that help explain why many churches fail to live out their original purpose or generate the kind of transformative impact the Gospel calls for:

- An escapist theology that emphasizes Christ’s second coming and our vertical relationship with God, while minimizing our horizontal responsibility to our neighbor. This view reduces the church’s role to merely rescuing souls from the fires of hell and avoiding the corrupting influence of “the world,” rather than engaging it redemptively.”

- A distorted framework of what constitutes a “healthy church,” where health is primarily measured by church attendance, buildings, and financial offerings. This leads to an event-driven ecclesiology focused on creating impressive worship experiences rather than aligning with the Great Commandment and the Great Commission.

- A lack of transformational discipleship, where churches often prioritize knowledge over character, and information over spiritual formation. Few faith communities are focused on actively making disciples who live out their faith in every area of life—including addressing the social and communal challenges around them.

- Superficial theological formation, where biblical teaching is shallow and ungrounded. This creates space for what might be called “junk theology,” centered on prosperity and emotional experiences rather than Christ-centered, theologically sound formation that equips believers for holistic faith and mission.

- The influence of prosperity theology, a radical reinterpretation of the Bible that treats material wealth as the ultimate sign of divine blessing. It focuses on personal economic growth while ignoring the need for community transformation.

- A consumer-driven, building-centered church model, in which congregants are treated as consumers of attractive religious events and spiritually entertaining experiences. This focus undermines the church’s integral mission and service to the community, resulting in shallow worship disconnected from and active, living faith that impacts life and one’s surroundings.

- A liturgy-centered view of church, where Sunday services and religious events dominate the church’s identity, pushing aside its missional calling. As a result, congregations become inward-looking, prioritizing worship activities over outward engagement and the pursuit of holistic transformation—spiritual, social, and economic—in their communities.

- Hierarchical and personality-centered leadership models, where pyramid-like structures elevate leaders to near-untouchable figures, fostering personality cults. Instead of nurturing humble, servant-hearted leadership modeled after Jesus, many church leaders adopt narcissistic leadership styles that crave admiration more than they reflect servant leadership.

- A disconnect from the living presence of God, where many believers are no longer led into spaces of being filled, empowered, and transformed by the Spirit of the living God. Genuine encounters with God are replaced with religious routines, emotional performance, or purely intellectual content. As a result, the church often fails to nurture Spirit-led communities marked by a deep longing for—and experience of—God’s presence, which should naturally lead to transformed, missional living.

- The normalization of abusive patterns in church life, such as spiritual abuse, emotional manipulation, and fear-based control. These behaviors often hide behind language of obedience or spiritual authority but ultimately suffocate the freedom, dignity, and calling God has given to every person. Rather than cultivating communities where people flourish and live out their vocation, such environments reproduce controlling cultures that contradict the liberating message of the Gospel.

Fruits of this Reality: Disconnection, Dualism, and Spiritual Poverty

The fruits of this reality reveal a deep disconnection from God’s holistic mission. Many churches have turned inward, prioritizing rituals, internal structures, and internal agendas over a genuine commitment to their calling to serve and transform their communities. This inward retreat reflects a loss of confidence in the power of the Gospel to bring about real and lasting change—in individuals and in society. Rather than becoming an embodied force of Shalom, the church often functions as a closed space, where the message of the Good News is reduced to spiritual formulas with little relevance to daily life.

As a result, a scarcity mindset and a sense of inferiority have taken root, producing churches that are servile, overly dependent on political alliances or rigid denominational structures. This posture is often rooted in a dualistic worldview that separates the spiritual from the earthly, hindering a holistic vision of the Kingdom of God and weakening the church’s ability to act with relevance in the world. The result is spiritual barrenness: activities, numbers, and events may abound, but there is little evidence of genuine transformation. The phrase “much foliage but little fruit” aptly describes the reality of many congregations which, despite outward vitality, fail to produce a tangible impact in the lives of their members and the communities they are meant to serve.

The Urgency of Rethinking Our Missiology, Ecclesiology, and Liturgy

All of this should lead us to deep reflection: What kind of church are we becoming? What kind of discipleship are we forming? What gospel are we embodying? What impact are we making in the world around us?

The key to answering these questions—and to transforming the current reality facing the Latin American church—lies largely in leadership and in a renewed understanding of what it means to be a healthy church engaged in truly transformative discipleship. This requires the courage to rethink prevailing paradigms of leadership, theology, missiology, and ecclesiology, so we can respond to today’s pressing challenges with honesty, clarity, and hope.

This article argues that the current design and self-concept of most churches is fundamentally inadequate to produce the kind of deep transformation the Gospel envisions. Their institutional identity and structures often limit their ability to live out that radical calling. While we may affirm Bill Hybels’ well-known declaration that “the local church is the hope of the world,” it must also be acknowledged that the way many churches currently function, organize, and understand themselves prevents that potential from being realized. By design, they are not equipped to bear such fruit—because nothing can produce what it was never designed to produce.

What kind of church are we becoming?

What kind of discipleship are we forming? What gospel are we embodying?

What impact are we making in the world around us?

More than 50 years have passed since the vision of misión integral (holistic mission) was first articulated in Latin America. Yet many churches have still not embraced it. This is not due to a lack of information or access to relevant theological frameworks, but rather because their ecclesiological self-understanding and organizational models are not aligned with that mission. In other words, we cannot live out or embody what has not been integrated into the very identity and vocation of the church. In the following pages, we will explore the roots of this disconnection and crisis, and propose a broader, biblically grounded definition of the ekklesia—one that recovers its original purpose and mission. The goal is to help us rediscover and become the kind of church Jesus envisioned: a restorative, disciple-making, worshiping, and transformative community, sent into the world to embody the Kingdom of God with power, compassion, and truth.

The Following Problem Tree Illustrates the Challenges Previously Described:

Part 2: What is the Ekklesia? – The Calling and Purpose of the Ekklesia

Introduction: Different Ecclesiastical Models

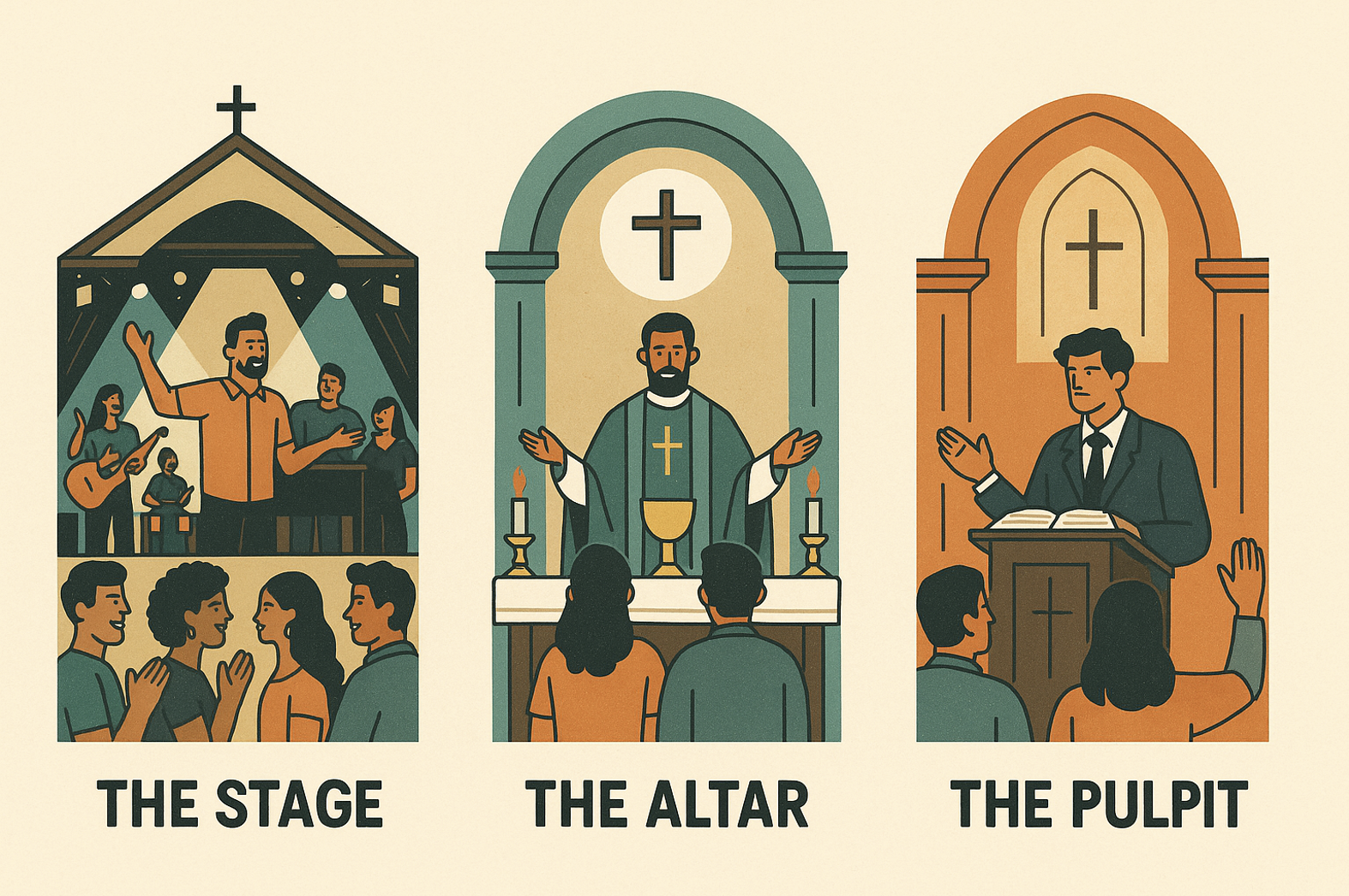

Many Christians today think of the church primarily as the building where they gather—a place to sing songs of praise, listen to preaching, and briefly connect with other believers. In practice, most church structures today are shaped by three dominant models that define their focus and approach to ministry:

- The Stage – The Worship Experience and Charismatic Leadership Model: Originating primarily in the United States, the Stage model revolves around a dynamic worship experience centered on performance and charisma. The focus is often on a powerful preacher, a visually striking stage, a vibrant worship band, and services enhanced with lights, sound, and multimedia—designed to attract and inspire attendance. This model typically includes a wide range of programs and events aimed at fostering engagement and excitement. With its emphasis on emotional experience, relevant preaching, and strong pastoral personalities, the Stage model has been widely adopted across Latin America—particularly within neo-Pentecostal, charismatic, and non-denominational churches. While it often succeeds in drawing large crowds and creating an atmosphere of enthusiasm, its challenge lies in sustaining deep discipleship, community formation, and social transformation beyond the stage.10

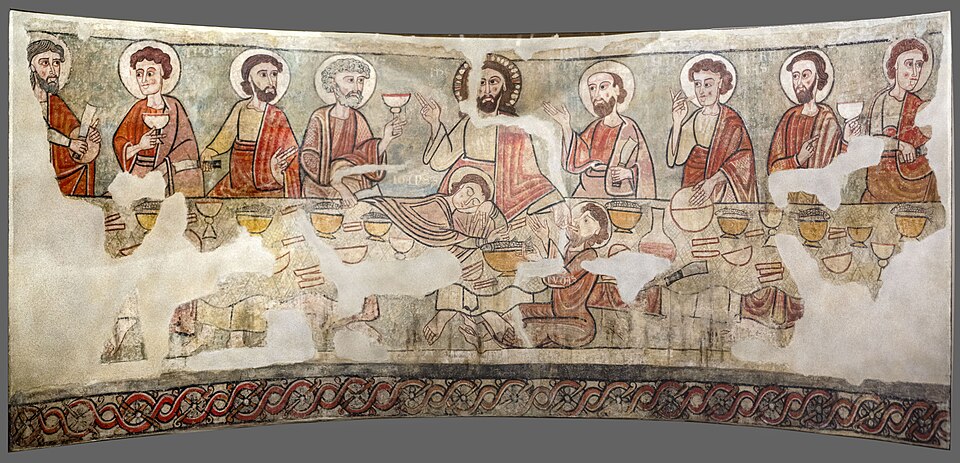

- The Altar – The Liturgical and Sacramental Model: Rooted in the ancient traditions of the Catholic, Orthodox, and Anglican churches, the Altar model centers the community around the celebration of the Eucharist or Holy Communion. The altar becomes the heart of worship, symbolizing the presence of Christ and the continuity of the Church through time. The liturgy—structured with prayers, readings, and rituals—anchors believers in the sacred rhythm of confession, word, and table. This model is rooted in the conviction that sacramental participation in the body and blood of Christ lies at the heart of church life—fostering an encounter with divine grace that nourishes both faith and unity. It highlights continuity with the teachings and practices of the early apostolic church, emphasizing reverence, mystery, and theological depth as vital expressions of ecclesial life.

- The Pulpit – The Preaching and Biblical Teaching Model: Typical of many Reformed and evangelical Protestant churches, the Pulpit model places the proclamation of the Word at the center of church life. The pulpit serves as both a symbol and a platform for authority, instruction, and spiritual nourishment. Expository preaching and rigorous study of Scripture form the backbone of Sunday gatherings, shaping the congregation’s theology, ethics, and mission. This model emphasizes doctrinal clarity, intellectual engagement, and the practical application of biblical principles to daily life. While it has produced generations of biblically literate believers and teachers, it can struggle when preaching becomes disconnected from community practice or when formation remains primarily cognitive rather than holistic and relational.

These models have undoubtedly blessed millions of people throughout the centuries and contain many valuable elements. Yet they share a common limitation: they tend to center the life of the church around the Saturday or Sunday service while relegating its local mission to the margins. The emphasis often falls more on what happens inside a building or liturgical space than on embodying God’s mission and forming an active, missional community committed to the holistic transformation of its surroundings and tangible impact in local neighborhoods. As a result, many congregations have adopted a mindset of “going to church” rather than “being the Church.” The danger of this approach is that the church can become not a living and transformative body, but a kind of Administrative Bureau of Liturgical Services (ABLS)—an institution preoccupied with religious programs and events, yet detached from its calling to be salt and light in the city. Yet we must ask: Is this the Church Jesus envisioned?

Today, a different way forward is emerging—one that reclaims the church as a shared life and a movement of presence in the city, rather than a scheduled event. The metaphor of the Table captures this vision powerfully. In contrast to the pulpit, altar, or stage, the Table represents the place where faith, community, and mission converge. It is not confined to a temple or sanctuary but extends into homes, streets, cafés, workplaces, and neighborhoods—spaces where life unfolds and relationships take root. Throughout the Gospels, Jesus revealed the Kingdom of God around tables—sharing meals with sinners and disciples, with the poor and the powerful alike. At the table, social hierarchies dissolve, strangers become guests, and ordinary acts of eating and conversation become sacraments of grace. In this sense, the table is not merely a metaphor but a missional posture—a way of being present to God and neighbor. To be the church as table means to practice hospitality as mission, discipleship as shared life, and leadership as servanthood. It signifies a shift from institution to movement, from spectators to participants, from consumers to co-laborers, from Sunday gatherings to everyday presence. Here, breaking bread and listening to one another are as essential as preaching and singing; prayer and justice flow naturally into one another. In an urban world marked by fragmentation, loneliness, and inequality, the table offers a vision of the ekklesia as a reconciling community—a people sent to embody shalom in the everyday life of the city. It is here that the church most faithfully reflects its Founder: Jesus, who still meets humanity at the table and sends His friends from it to heal the world.

This emerging vision points toward the kind of ekklesia our cities desperately need—one that is relational in essence, incarnational in practice, and transformational in impact. It invites us to return to Jesus’ original intention for His community, and it raises a central question this article will explore in the pages ahead: What kind of Church did Jesus envision and dream of?

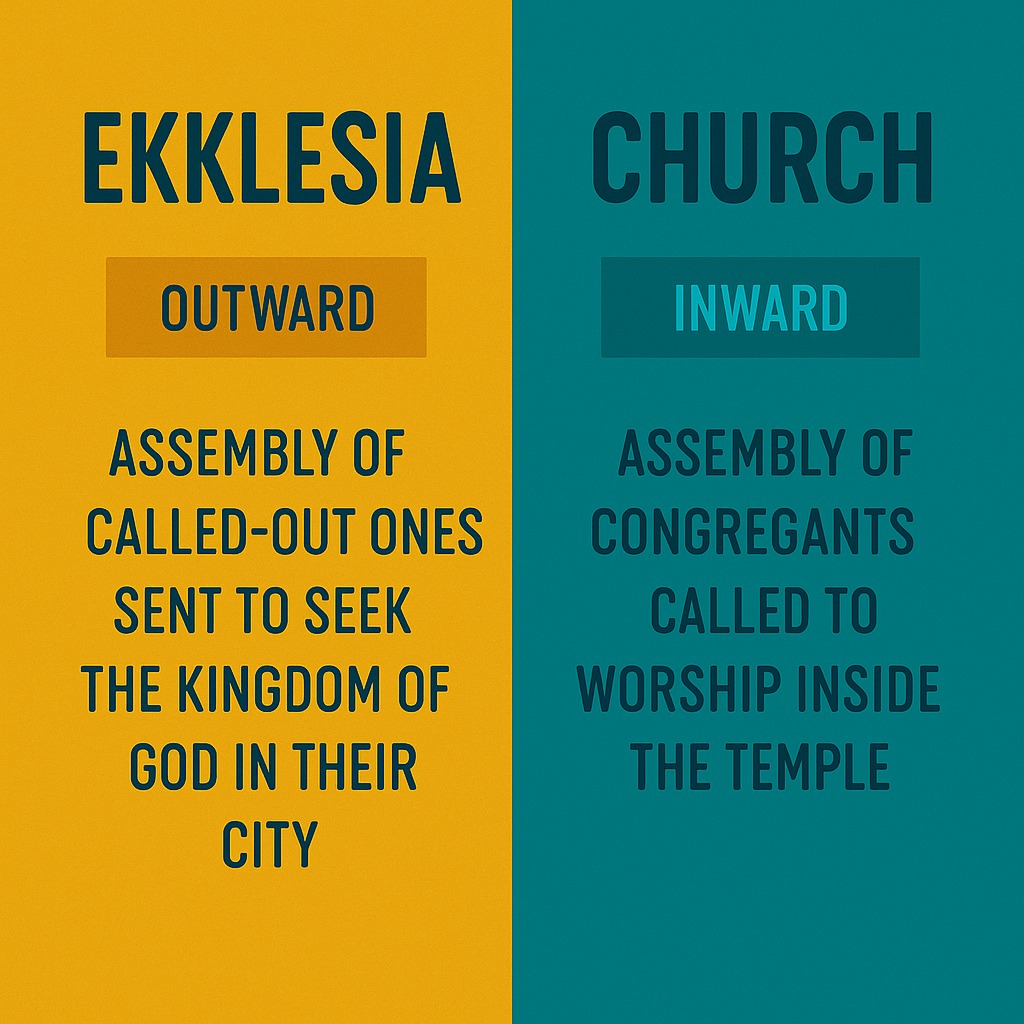

The Original Meaning of Ekklesia

Unfortunately, many people today view the church merely as a harmless, worshiping, evangelizing, and servile community. Others, by contrast, see it in a far more negative light—as a controlling, toxic, or indoctrinating institution that seeks to suppress independent thought and maintain power. Yet if the church had truly been only one of these things—harmless or oppressive—it is unlikely it would have faced the fierce persecution it endured in its earliest days. When Jesus used the word ekklesia to describe the community of disciples He intended to form, He had something quite different in mind than the modern connotations often associated with the word church. So, how should we truly define the term ekklesia? To answer that, we must first explore what Jesus envisioned when He established the ekklesia. Let us begin with a brief recap of His purpose and mission.

The Purpose and Mission of Jesus

Jesus came to proclaim the Good News and to establish the Kingdom of God on earth. He healed the sick, announced the gospel, confronted injustice, forgave sins, gathered a community of disciples, and revealed to us the dream of God. But His mission did not end there: He died and rose again—and in doing so, He rescued us from the power of sin and death, which prevent us from experiencing God’s Shalom in our lives and in the world. His death and resurrection marked a definitive turning point, as Jesus defeated once and for all the most powerful weapon Satan wielded over creation: death itself—along with the forces of chaos and destruction. As Scripture declares: “Where, O death, is your sting? Where, O grave, is your victory?” (1 Corinthians 15:55–57). Through Christ’s resurrection, life—and life in abundance—has the final word and will be established as the ultimate reality of our universe (John 10:10). Even death has lost its power.

In addition to proclaiming the gospel of the Kingdom of God, Jesus called together a group of disciples to form a radically different kind of community—one grounded in faith and trust in God—which He Himself called ekklesia (Matthew 16:18; Matthew 18:17). But what exactly was the ekklesia during Jesus’ time—a term that had already been part of Greek and Roman political vocabulary for centuries?11

Historical Context: Temple, Synagogue, Sanhedrin, and Ekklesia

Before defining the term ekklesia, it is important to understand the broader institutional context of Jesus’ time. During His earthly life, four main institutions shaped the religious, social, and political life of Israel:

- The Temple was the central place of worship in Israel—the location where the people encountered the presence of God through sacrifices and priestly mediation. It was the only place where the rituals prescribed by the Law could be performed, making it the most sacred space in the Jewish religious imagination—the very heart of national religious life.

- The Synagogue served as a local gathering place for teaching and community life. Unlike the Temple, which was centered on sacrificial rituals, the synagogue provided accessible spaces for studying Scripture, prayer, and to strengthen communal identity. It enabled local communities to be spiritually nourished and grow through the reading and interpretation of the Law and the Prophets.

- The Sanhedrin (or council of seventy elders) was the highest judicial and legal authority in Israel. It oversaw legal matters, upheld the application of the Law, and maintained institutional cohesion. In addition to the Great Sanhedrin based in Jerusalem, smaller regional courts—known as “lesser Sanhedrins” or batei din—operated in major towns to address legal disputes and oversee justice at the local level.

- The Ekklesia referred to an assembly of citizens “called out” of their homes by a herald to meet in a public space. In the Greco-Roman cities, this assembly was responsible for regularly convening to deliberate on civic and political matters—discussing laws, electing magistrates, and making decisions on the public affairs of the city.12

While in Galilee or Judea during the time of Jesus the ekklesia did not function exactly as it did in the classical Greek polis (city-states), certain cities with stronger Hellenistic influence—such as those in the Decapolis, Tiberias in Galilee, or Sepphoris (located just 6–7 km from Nazareth, where Jesus grew up)—retained assembly-based structures inspired by that tradition. In these cities, local elites would gather to deliberate on municipal matters, though their decisions were subject to the authority of the Roman government (or the local tetrarch, in the case of Galilee), and they were required to respect Jewish law as it pertained to the local population. Nevertheless, the concept of ekklesia was familiar in the region, and as the disciples began to move beyond Galilee into Samaria and other parts of the Greco-Roman world, they encountered it more frequently. In fact, the term ekklesia appears 114 times in the New Testament, highlighting its central importance for the emerging community of Jesus’ followers.

This is why it is essential to understand Jesus’ intention in choosing the word ekklesia to describe His community of disciples. Unlike temple or synagogue, the term ekklesia in Jesus’ time did not carry religious connotations—it was a civic and political term. Its origins trace back to Greek democracy, where it referred to the governing assembly or legislative body of citizens responsible for the administration of the city-state. The ekklesia was composed of men aged eighteen and older who had completed at least two years of military service—indicating a high level of commitment to their city. In most Greek cities, the ekklesia met regularly to deliberate on public and governmental matters, ensuring good governance, development, and the well-being of the city and its future.Thus, ekklesia did not simply mean a “gathering”; it referred to an official assembly with the authority to make decisions, implement policies, and shape the public life of the community.13 This system of citizen participation—what we know as democracy or “rule by the people”—was a hallmark of ancient Greece and had no precedent in other civilizations of Asia, Africa, or Europe at the time.14 In the current Mexican context, a concept that bears some resemblance to the Greek ekklesia would be the COPACI (Citizen Participation Council), a local council aimed at involving citizens in decision-making processes for the well-being of their communities.

When the Roman Empire—with its hierarchical structure—took control of the Hellenistic territories, it allowed many cities with Greek traditions to retain their local institutions, including the ekklesiai, as long as these did not conflict with imperial interests.15 In this way, Rome gradually integrated the Hellenistic cities into its imperial system, delegating key administrative functions to local elites. These elites, organized into formally recognized civic bodies—such as municipal councils (ordines decurionum)—not only represented the interests of their communities but also served as agents of Roman authority. Through these local bodies, Rome ensured the enforcement of its laws, the promotion of its culture, and the fulfillment of its imperial priorities.16 Their responsibilities included tax collection, local justice administration, military recruitment, and the execution of public works.17 While these governing bodies—including the ekklesiai—retained some traditional elements of civic autonomy, their most significant decisions—particularly in political, military, or fiscal matters—required the approval of the provincial governor or imperial magistrates appointed by the emperor. In this way, Rome maintained control over its conquered territories through strategic collaboration with local elites, thereby ensuring the stability and expansion of its power throughout the provinces.

Against this imperial backdrop, Jesus’ use of the term ekklesia takes on much deeper meaning and subversive weight.18 Even under Roman oversight and nominally tasked with serving imperial interests, the ekklesia still evoked the idea of a citizen assembly—vested with authority to deliberate and make decisions for the well-being of the city. Jesus’ appropriation of this term suggests not a retreat from civic life, but the formation of an alternative public community empowered to embody the values of the Kingdom of God.

Why Jesus Chose the Word ‘Ekklesia’

It is worth emphasizing again how profoundly revealing it is that Jesus and the apostles chose a secular term—ekklesia—rather than a religious one to define the identity and purpose of the community they were forming. Jesus could have said, “I will build my Temple” or “I will build my Synagogue,” referring to the two central religious institutions of Judaism in His day. But He didn’t. By choosing ekklesia, He intentionally distanced Himself from a model centered on traditional religious structures. His vision went far beyond an internal reform of Judaism; it relocated the spiritual center—not to a sacred building—but to a living, gathered community in His name, present across the world.

In this light, Jesus’ vision of the ekklesia can be understood as a continuation and expansion of the Old Testament concept of qahal (קָהָל)—the assembly of Israel called by God to be “a kingdom of priests” (Exodus 19:6), tasked with reflecting and mediating God’s presence in the world.19 This priestly dimension, in turn, reaches back to the creation narrative, where Adam and Eve are entrusted with the responsibility to rule and steward the earth on God’s behalf (Genesis 1:26–28). The Spirit “hovering over the chaotic waters” in Genesis 1:2 symbolizes God’s creative impulse to transform chaos into a world of life and order. In this cosmic vision, all creation is understood as a cosmic temple, and human beings—first Adam and Eve, then Israel as qahal—are called to serve as priestly stewards who embody God’s presence and advance order, fullness, and justice on the earth.20

Jesus takes up and redefines this original calling by establishing His ekklesia: a universal and radically inclusive assembly made up of people from every nation, ethnicity, and background. Its mission is not to build temples but to be the temple—not to centralize spirituality in a specific location, but to disperse it like yeast throughout all of society. Just as the Spirit moved over the primordial chaos to bring order and life to the world, so the ekklesia, empowered by that same Spirit, is sent to confront the forces of disorder—violence, injustice, and alienation—by creating spaces of worship, reconciliation, and justice, and by permeating its surroundings with the presence of the God of Shalom. This thread of continuity—from the vocation of Adam and Eve, to Israel’s calling as qahal, to Jesus’ commission to His ekklesia—reveals a singular divine project: the restoration of creation through the formation of a people who radiate God’s presence and Shalom in the midst of a chaotic world.

Just as the Spirit moved over chaos to bring about order and life, the ekklesia, empowered by that same Spirit, is sent to confront the forces of disorder—such as violence, injustice, and alienation—creating spaces of worship, reconciliation, and justice, and saturating its surroundings with the presence of the God of Shalom.

In light of this, Jesus’ choice of the word ekklesia was no accident—it was deliberate. By adopting a term rooted in civic and political life—not in religion—Jesus was radically redefining what it means to be a spiritual community. His ekklesia would not replicate imperial models of power, but would instead be an alternative assembly, “called out” and summoned not by a human emperor, but by the King of kings. Its mission: to manifest the presence of God, embody His reign amid broken human systems, confront evil in all its forms—spiritual, social, cultural, and structural—and sow signs of the Kingdom into every sphere of life.

Imbued with the DNA of the Kingdom and empowered by the Holy Spirit, the ekklesia was conceived as a living, dynamic, and transformative community—representing the interests of heaven in the midst of the earth. It is a restored people, commissioned to act as ambassadors of the Kingdom of God (see 2 Corinthians 5:17–21 and Ephesians 3:10). For this reason, its identity is not confined to a Sunday gathering. It unfolds throughout the entire week, across all areas of life. Jesus’ use of the term ekklesia thus powerfully redefines the identity, purpose, and mission of His disciples: a sent people, commissioned to disciple individuals, cities, and nations—proclaiming with both word and deed the Shalom of the Kingdom.21

Part 3: How Did We Get from Ekklesia to “Church”?

If, for Jesus and His apostles, ekklesia truly meant the assembly of citizens of God’s Kingdom —empowered by the Spirit to represent that Kingdom on earth—then how did we arrive at the way we understand the word church today? How did this term come to be associated primarily with a place of worship, an ecclesiastical building, or an institutional religious structure, rather than with a vibrant, active, and missional community committed to seeking the shalom of its context?

How Linguistic Evolution Changed the Meaning from Ekklesia to Kuriakē to “Church”

A significant transformation in the meaning of ekklesia began in the fourth century, when Jerome translated the Greek word ekklesía into Latin as ecclesia in his Vulgata. Following the Edict of Milan (313 AD), which legalized Christianity under Constantine, this term gradually evolved in both meaning and use. Once denoting a Spirit-empowered assembly called out to embody God’s reign in public life, ecclesia took on the tone and structure of the Roman world—becoming more institutional and hierarchical, consistent with the Empire’s legal and political culture.

Over time, ecclesia came to designate not only the community of believers, but also the place of worship and the institutional framework of the Church—its buildings, clerical offices, and sacramental system. The church’s identity slowly shifted from a dynamic movement to a centralized structure aligned with imperial power. The translation itself, though linguistically accurate, subtly redefined how Christians imagined the people of God: from a people on mission to an institution that mediates grace. This linguistic and theological shift had far-reaching consequences.

- It reinforced a clerical divide between ordained leaders and lay participants.

- It sacralized space and ritual, locating holiness in the temple rather than in the community.

- It diminished the missional dynamism of the New Testament ekklesía—a people called out to embody God’s Reign in the world.

This reorientation profoundly shaped the Western imagination of “church,” influencing Christian notions of leadership, belonging, and mission for centuries.

The evolution continued in the Romance and Germanic languages. The Spanish iglesia stems directly from ecclesia, whereas the English church and German Kirche derive not from ekklesía but from another Greek term—kuriakē (or kuriakon)—meaning “belonging to the Lord.” By the fourth and fifth centuries, Greek-speaking Christians were widely using kuriakē to refer to “the Lord’s house”—or the place of worship where the Lord’s Supper was celebrated. This reinforced the perception of the church (as well as the Iglesia) as a liturgical space rather than a community sent into the world.

Interestingly, the term kuriakon appears only twice in the New Testament—once for the “Lord’s Supper” (1 Corinthians 11:20) and once for the “Lord’s Day” (Revelation 1:10)—yet in later usage it became synonymous with Christian gatherings and eventually with buildings of worship. This shift was sealed when the Goths translated “Kyriakos oikos” (the Lord’s house) into the Germanic ciric, which later became kerk in Old English and eventually church in English and Kirche in German.22 Thus, through this chain of linguistic transformations—from ekklesía to ecclesia to kuriakē—the meaning of “church” moved from a participatory, Spirit-led people to an institutional and spatial concept.

From Movement to Monument: The Institutionalization of the Ekklesia

When translators replaced ekklesía with terms like church, Kirche, or Iglesia (which is conceptually much more aligned with church than with ekklesia), much of its original meaning was lost. Even the Reformation’s linguistic corrections—such as Martin Luther’s choice of Gemeinde (“congregation”) instead of Kirche to refer to the ekklesia—could not fully recover the dynamic vision of a Spirit-led community sent into the world. The focus largely remained on a congregation gathered for weekly worship and teaching.

As a result, the rich biblical concept of ekklesía—a living assembly empowered by the Spirit, engaged in the well-being of its city—was gradually reduced to a periodic religious gathering within a building. What began as a movement of the Spirit became, over time, a monument of religion—institutionalized, domesticated, and often detached from its mission to embody and advance the Kingdom of God in every sphere of life.

Consequently, ekklesía became sacralized and increasingly confined to the spiritual and religious dimensions of Christianity. In many traditions—Catholic, Orthodox, and Anglican—the liturgy centers on the Eucharist, while in Protestant, Evangelical, and Charismatic churches, the focus shifts to the pulpit or stage. Across these forms, the “church experience” has become synonymous with attending a weekly service (i.e. “going to mass,” or “attending a Sunday service”) rather than participating in a vibrant, transformative community.

When Religious Meetings Replace the Missional Community

As a result of this evolution, many—including Christians from the Anabaptist-tradition, who rejected clerical hierarchy and emphasized community-led leadership—now understand ekklesia as the assembly of saints: a people set apart from worldly structures to belong to God’s own. From this perspective, ekklesia is conceived as a community separated from its surroundings; gathered primarily for prayer, sacraments, and teaching to cultivate lives of holiness, consecration, and separation from the world’s influences.23

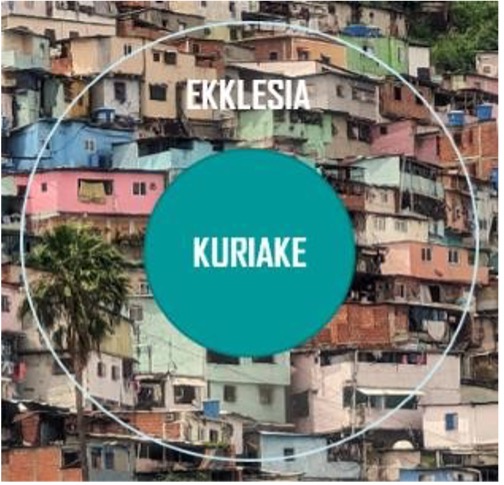

We might conclude, then, that most churches today operate more as kuriakē than as ekklesia. Even many church-planting movements focus more on establishing kuriakēs—congregations centered on worship and teaching—than on forming ekklesias: communities sent to transform their surroundings. While kuriakē—with its emphasis on worship, preaching, and communion—is essential to Christian life, it does not encompass the fullness of the church Jesus envisioned. Kuriakē functions within the ekklesia, but the ekklesia holds a far broader purpose. Undoubtedly, it’s essential for believers to gather in Jesus’ name for worship and fellowship. Yet reducing the ekklesia to a mere religious meeting—or worse, a building—strips it of the purpose Jesus established. The original ekklesia was not confined to temples or weekly gatherings; it was a missional movement, set apart to participate in God’s mission. It was a community sent into the world to witness God’s Kingdom amid cultures that had replaced the truth of the Gospel with other narratives. It was an assembly of disciples committed to the life of the city—dedicated to confronting injustice and called to embody God’s story through word and deed.

This is precisely why Jesus chose a non-religious term for his community of disciples. He wasn’t interested in merely forming a spiritual congregation gathered around a stage, pulpit, or altar. His vision was a community committed to the holistic well-being—the shalom—of its surroundings. Just as the Greco-Roman ekklesia bore responsibility for its polis’s common good, so too Jesus’ Spirit-empowered ekklesia was called to be an instrument of God’s Kingdom: set apart from the world in ethics, values, and purpose, yet deeply engaged in transforming people, communities, and nations. Its mission encompassed making disciples, creating spaces of belonging and connection with God, healing and restoration, and advancing peace and justice throughout society.

In light of this, let’s reflect on four essential aof the ekklesia that can help us refocus our mission and recover Jesus’ vision:24

- The Ekklesia as a Healing and Missional Community.

- The Ekklesia as a Spirit-Driven Disciple-Making Movement.

- The Ekklesia as a Transformative Force.

- The Ekklesia as a Worshiping Community in Communion with God.

Part 4: The Ekklesia: A Healing and Missional Community

Sent as Christ: The Comprehensive Mission of the Ekklesia

In John 20:21, Jesus declares: “Peace be with you. As the Father has sent me, so I am sending you.” This commission establishes the church as a sent community to continue his comprehensive mission. The ekklesia is called to be an ambassador of the Kingdom—proclaiming and embodying the Gospel in every sphere of society.

Jesus came not merely to save individual souls, but to redeem persons, restore entire communities, and reconcile the entire cosmos under God’s lordship. As expressed in John 3:16-17, one of the most well-known biblical passages: “For God so loved the cosmos—the whole of humanity, the created order, and even worldly systems with their values—that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life. For God did not send his Son into the cosmos to condemn the cosmos, but to save the cosmos through him.” Similarly, Paul affirms in Colossians 1:19-20: “For God was pleased to have all his fullness dwell in Christ, and through him to reconcile to himself all things—whether things on earth or things in heaven—making restorative peace through the blood of his cross.” Together, these passages reveal the breathtaking scope of Jesus’ mission—and therefore of his ekklesia: to serve as agents of reconciliation and transformation throughout all creation.

In other words, the ekklesia exists not to serve itself, but as an instrument through which God acts in the world.25 This is where ekklesia’s original meaning becomes profoundly significant: understood as “an assembly of Jesus-followers, set apart to participate in God’s mission, reflect His Kingdom, and seek the shalom of the city,” our calling extends far beyond gathering for worship and edification. We are commissioned to fully live and embody the Gospel beyond the four walls of church buildings. Sent into the world, we bear collective responsibility to guide our communities and cities toward a better future—bringing God’s shalom to every sphere of human existence.26 In short, the idea that life is a pilgrimage from a lost paradise toward a new and restored home is a powerful metaphor woven throughout the entire Bible. It deeply reflects the ekkelsia’s calling: to be a people on the move, who actively anticipate and participate in the restoration of all things.

The Table as a Place of Mission

It’s important to recognize the ekklesia’s growth during Christianity’s first three centuries was fueled, partly by Jesus’ strategic use of existing social practices—especially shared meals. This reality echoes Luke’s description of the post-Pentecost community: “They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching, to fellowship, to the breaking of bread, and to prayer” (Acts 2:42). These weren’t occasional events but a constant rhythm of life. Sharing meals together permeated early church life. These meals were more than social gatherings—they became sacred assemblies. Tables were transformed into inclusive spaces, unlike the more exclusive environments of the temple or synagogue, enabling the ekklesia to engage fully with daily life without withdrawing from the surrounding society. In doing so, Jesus turned tables into pulpits and homes into assembly halls, where strangers were welcomed and often became disciples. The ekklesia didn’t merely speak about belonging—it lived it. Through bread, wine, the Word, and presence, it formed communities where every person could find a place, a purpose, and a family. In our fragmented urban world, recovering this table-centered vision could reshape how the church engages its neighborhoods—transforming ordinary meals and shared spaces into frontlines of mission and reconciliation.

Jesus turned tables into pulpits and homes into assembly halls where strangers were welcomed and often became disciples.

Koinonía as a Way of Life

For the early ekklesia, the Greek term koinonía—typically translated as “communion” or “fellowship”—signified far more than spiritual closeness or emotional affection. It described a deeply committed shared way of life, and meant active and tangible participation in the lives of others: meeting each other’s material needs (Acts 2:44–45), partnering in the proclamation of the gospel (Philippians 1:5), making disciples of all nations (Matthew 28:18–20), sharing in the sufferings of Christ (Philippians 3:10), and walking in obedience to God’s call (1 John 1:6–7). At its core, this radical form of fellowship had one ultimate purpose: to glorify God.27

As Paul himself declared, when the ekklesia lives out koinonía—a community marked by mutual love, service, and shared purpose—it demonstrates a radically countercultural reality. By living out the Gospel in community, God reveals His eternal wisdom and plan not only to people, but to the unseen powers and authorities of the universe (Ephesians 3:10).

The ekklesia, then, is not merely a harmless religious group; it is a living signpost of God’s transformative Kingdom. Just as the Kingdom was present in Christ’s person, it is now made present through His body—the ekklesia. This is why Paul urged believers to “clothe yourselves with Christ” (Romans 13:14)—to live in such a way that Christ becomes visibly present through them. This identity carries a profound mission: to embody the integral mission of Jesus. Having been reconciled to God, the ekklesia is now called to be an ambassador of that reconciliation. Its task is not limited to proclaiming with words—it must also embody, through action, the love that restores, the grace that forgives, and the hope that renews. Where there is division, the ekklesia is called to build bridges; where there are wounds, to bring healing; where there is oppression, to sow justice. As Christ’s visible body on earth, the ekklesia declares through its very existence: All things can be made new (2 Corinthians 5:17–20).

The Ekklesia as the Soul of the City: A Visible, Sent, and Incarnational Community

From this perspective, God’s Kingdom is inseparably linked to a concrete people—God’s own people. Jesus didn’t come merely to deliver a set of written or propositional truths about God, as if His mission were to leave behind a book. Instead, He called and gathered a living, breathing community of men and women to bear witness to who he was and embody His life, words, and works. The new reality He launched in history was meant to continue not primarily through a text, but through a living, incarnational, missional community.28 Thus, the ekklesia—as Christ’s visible body in the world—proclaims through its existence that all things can be made new – both anticipating and participating in the coming Kingdom. This incarnational presence proved revolutionary. As historian Rodney Stark observes: “To cities filled with the homeless and impoverished, Christianity offered charity as well as hope. To cities filled with newcomers and strangers, Christianity offered immediate fellowship. To cities torn by violent ethnic strife, Christianity offered a new basis for social solidarity.”29

The Epistle to Diognetus, written around A.D. 130, beautifully captures the early church’s vision of its role in society: “What the soul is to the body, Christians are to the world.”30 This powerful statement reflects how the first Christians saw themselves—not as a mere appendage to society, but as its very soul: essential to its moral, spiritual, and social well-being. They were not concerned with political power—indeed, they had none. Instead, their posture was shaped by the cross: a life marked by compassion, sacrificial service, and spiritual power offered in service to their cities. As a result, they sought to imitate Christ by tangibly expressing God’s love to those in need—the poor, the enslaved, widows, and the sick—especially during times of crisis. This way of life set them apart in the Greco-Roman world, where they were simultaneously ridiculed and admired for their righteousness, compassion, uncompromising mercy, and practical love of neighbor. It was precisely this concrete embodiment of the Gospel that fueled the exponential growth of the ekklesiai during the third century. They understood that their mission was not merely to hold gatherings, but to become shalom-generating communities—the soul of the city—living, visible, and sent expressions of God’s reconciling and renewing presence in the world.31

This is what it means to be the ekklesia Jesus envisioned: a transformed and transforming community, empowered by the Spirit, sent into the world to live out, proclaim, and extend the Kingdom of God.

This holistic vision of mission is echoed by South African missiologist David Bosch, who writes:“The mission of the church, then, encompasses all the dimensions and scope of Jesus’ ministry and must never be reduced to church planting or saving souls. It involves proclaiming and teaching, but also healing and delivering, showing compassion to the poor and the oppressed. Like Jesus, the church is sent into the world—to love, serve, preach, teach, heal, save, set free, intercede, embody the message, become servants, remain open even to suffering or death, to worship, and to be attentive to the guidance of the Spirit.”32 This is what it means to be the ekklesia Jesus envisioned: a transformed and transforming community, empowered by the Spirit, sent into the world to live out, proclaim, and extend the Kingdom of God.

Part 5: The Ekklesia – A Discipling Movement Moved by the Spirit

From Fear to Mission: The Encounter with the Risen One

After Jesus’ death, the disciples were discouraged, hiding in fear, and overwhelmed with despair. Their world had collapsed. The one they had followed as the Messiah—the one who spoke with authority, healed the sick, and proclaimed the Kingdom of God—had been brutally crucified. Their hearts were filled with uncertainty and doubt. When the risen Jesus appeared to them, they didn’t recognize Him immediately. Some thought they saw a ghost. Then came His gentle yet direct challenge: “Why are you frightened? Why are your hearts filled with doubt?” (Luke 24:38).

To prove that He was truly alive, Jesus ate with them. He showed them His hands and feet. He invited them to touch Him—to be convinced that He was no ghost or illusion. “Why are you troubled?” He asked again. “Don’t you know that I have conquered death? Don’t you see that I am sending you with power from on high?” (Luke 24:39). In the days that followed, He opened their minds to understand the Scriptures through the lens of His Kingdom (Acts 1:3), and reminded them that the message of the Kingdom and His vision of shalom was to be proclaimed to all nations and every creature. Jesus didn’t just calm their fears—He commissioned them. He gave them a global mission: to disciple—to transform, influence, and model—a new way of life for the nations. A mission that, from a human perspective, seemed impossible. He sent them to announce that a new Kingdom had begun, a new reality under His lordship, the path toward the holistic shalom God had dreamed of since creation.

Discipling Nations: Jesus’ Master Plan

In Matthew 28:19–20, Jesus clearly defined the mission of His ekklesia: “Go and make disciples of all nations… teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you.” And what had He commanded? “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, and mind; and love your neighbor as yourself. All the Law and the Prophets depend on these two commandments” (Matthew 22:37–40). This is the essence of the disciple-making mission: to form communities where people learn to live out love for God, for others, and for themselves in every area of life. It is the starting point for embodying and extending the Kingdom—a Kingdom that is revealed through transformed lives, restored relationships, and healed communities.

Theologian and writer Brian McLaren, in The Secret Message of Jesus, offers a powerful summary of the different versions of the Great Commission (Matthew 28:18–20; Mark 16:15; Luke 24:49 / Acts 1:8; John 20:21) in this paraphrased reflection: “You cannot keep the good news of the Kingdom a secret. That’s why I’m sending you—just as the Father sent me—to share the good news of the Kingdom of God with the world. For everyone who receives and embraces this message, help them form communities where they can learn together by putting into practice what they’ve heard. In this way, little by little, they will learn to live by my teaching, just as you are still learning each day. But don’t try to do it alone. Don’t rely only on your own strength—trust in the power of the Holy Spirit. And don’t limit yourselves to your own people: cross borders, break down barriers, and share this message with people of every culture, language, and nation. What you’ve discovered by walking with me—the way, the truth, and the life—is for everyone.”33

In one of His final conversations with the disciples before ascending to heaven, Jesus laid out a clear strategy for the expansion of the Kingdom: “You will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, in all Judea, in Samaria, and to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8). The mission was to begin in Jerusalem—the religious, political, and economic heart of Israel—and then extend to Judea, move into Samaria (challenging cultural barriers and historical prejudices, given the region’s longstanding enmity with the Jews), and ultimately cross borders to touch the Gentile nations of the vast Roman Empire. This unfolding expansion carried a radical message: that Jesus—not Caesar—is the true Lord, and that His Kingdom of shalom confronts every form of idolatry, oppression, and violence perpetuated by the kingdoms and empires of the earth.

This mission was far from easy for the disciples—none of the places they were sent promised to be simple. Yet Jesus did not merely send them; He empowered them. In Matthew 28:20, He assured them, “I am with you always, to the very end of the age.” And in Luke 24:49, He instructed them, “Stay in the city until you have been clothed with power from on high.”

The Power of the Spirit: Not for Spectacle, but for Mission

The power of the Holy Spirit was never meant to be an end in itself, but the divine force that would propel the disciples to bear witness and advance God’s Kingdom among the nations—making disciples and raising up ekklesias committed to pursuing shalom in their communities. Today, however, in many circles, the Spirit’s primary purpose is often misunderstood—reduced to signs, wonders, spiritual gifts, charismatic manifestations, or emotionally charged experiences. While charismatic and Pentecostal communities have rightly helped recover a vibrant theology of the Spirit—one long diminished or sidelined in traditional Protestant and Catholic traditions—they have at times also missed the deeper aim of the Spirit’s work: to empower God’s people to embody and extend His reign of justice, mercy, and transformation.

Miracles and spiritual encounters often accompany the Spirit’s movement, but they are not the ultimate goal. They are signs that point toward something greater—the reality of the Kingdom. The central mission of the Spirit is to form a people who reflect God’s character and live out His purposes in the world. This means cultivating a community marked by justice, peace, and joy in the Spirit (Romans 14:17), where the fruit of the Spirit flows freely: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control (Galatians 5:22–23). These are not merely private virtues—they are public, relational, and cultural realities that shape how we live together in the world.

When the Spirit truly moves, He doesn’t merely stir emotions—He gives birth to new ways of living. The Spirit creates countercultural communities marked by generosity instead of greed, reconciliation instead of division, humility instead of domination. This is how shalom begins to take root: when the Spirit fills not just individuals, but entire neighborhoods, cities, and societies with the aroma of the Kingdom. In the end, the true substance of the Kingdom is not found in ecstatic experiences but in transformed lives and communities—shaped by righteousness, justice, reconciliation, and the renewing presence of the Spirit—where shalom becomes not just a distant hope, but a lived reality.34

The Missional Ekklesia: Communities that Disciple with Life

Jesus’ plan was to establish and strengthen missional ekklesias—Spirit-led communities that would live according to the values of the Kingdom and spread the Gospel of shalom throughout the earth. From the book of Acts to Revelation, we see the disciples’ unwavering commitment to this mission: to raise up disciple-making ekklesias that would embody the good news of the Kingdom in every part of the world. This was their core identity and purpose:

- They proclaimed the Kingdom of God and the lordship of Christ.

- They formed disciples who grew in trust and obedience to Jesus.

- They taught the way of Jesus and cultivated Christlike character.

- They sought to live out Kingdom values in every area of life.

- They loved and served their neighbors in tangible, practical ways.

- They developed leaders who carried the Gospel into new cultures.

- They challenged structures of sin and injustice, as well as ideologies opposed to the Kingdom of God.

Tragically, many churches today have reduced discipleship to spiritual activities: attending prayer meetings, listening to sermons, or participating in Bible studies. Though these are all good and necessary, true discipleship goes far deeper. It’s not enough to know Scripture – we must learn to live like Jesus in every sphere: at home, at work, in culture, community, economics, and politics. This is why any theology that presents the Gospel merely as a “spiritual escape” falls dangerously short – it ignores our mandate to disciple nations and transform fragile cities through the power of God’s Kingdom.

Ambassadors of the Kingdom: Multiplying Communities of Shalom

The crucial question remains: Do we truly trust the One who claims all authority in heaven and on earth? Are we willing to become the ekklesia He envisioned? The same Spirit who empowered the first disciples is still at work today. He longs to raise up men, women, youth, and children—filled with holy passion—ready to become part of God’s response to heal our broken cities and nations. We are called to multiply as Kingdom ambassadors, demonstrating through both words and actions that God’s Shalom is real and available to all. This is the ekklesia’s true vocation: to be a Spirit-led, disciple-making movement that transforms the world.

Part 6: The Ekklesia – A Transformative Community

The Gates of Hades: The Ekklesia’s Mission to Confront Death’s Forces

When Jesus declared in Matthew 16:18, “I will build my ekklesia, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it,” most modern readers interpret this in purely spiritual sense. Yet a deeper reading reveals Jesus envisioned his ekklesia as an active transformative force, called to storm death’s strongholds represented by “Hades’ gates.” This powerful declaration shows that neither visible nor invisible forces of death can withstand the ekklesia’s advance. Jesus isn’t merely promising spiritual protection – he’s redefining his community’s very purpose.

The ekklesia was never meant to be a passive institution, confined within four walls, and distant from society’s pain. Rather, it was called to be a living, active organism, constantly confronting the forces of destruction and oppression that threaten life, shalom, and justice in God’s created world. It is a dynamic assembly—called out and sent forth—to restore what is broken and to make the Kingdom of God visible in the midst of history.

It’s crucial to understand that in the ancient world, “the gates of Hades” were not merely a symbolic image of death or demonic forces. Historically, city gates functioned as vital hubs of public life—the epicenter of economic, political, judicial, and social activity. These were places where governmental decisions were made, military strategies were designed, alliances were forged, and legal disputes were settled (see Deuteronomy 21:18–21; 22:15; 25:7; Ruth 4:1–11; 2 Samuel 15:1–6; Amos 5:10–15). In essence, they served as the city’s command centers. Thus, when Jesus speaks of “the gates of Hades,” He isn’t referring only to spiritual or demonic forces but the organized powers of darkness and death, both spiritual and structural, including the human systems and power structures that perpetuate injustice, oppression, and dehumanization.35 When these “gates” are linked to the realm of Hades, they symbolize a network of visible and invisible powers operating from the very command center of death— spreading destructive influence to suppress—or even eradicate—the abundant life God desires for His creation.

In the face of this, Jesus boldly declares that these forces—whether spiritual strongholds or their tangible manifestations in corrupt systems, structural injustices, and mechanisms of exclusion—will not prevail against the ekklesia He is building. In other words, God’s Kingdom, made visible and operative through the ekklesia, will confront and overcome these structures – liberating the oppressed, exposing corruption in all its forms, and restoring life where death’s systems have ruled.

It is truly striking that Jesus does not call His ekklesia to retreat in the face of evil, but to advance with boldness. As He envisioned it, the ekklesia is not a passive or defensive community that hides from the world to protect itself from its influences. Rather, it is an active, offensive force—breaking into the world’s dark places with Kingdom light. It is not the forces of evil assaulting the “gates of the church”; instead, it is the ekklesia that storms the gates of Hades—determined, in the power of the Spirit, to bring freedom, healing, and justice where death once reigned. This is precisely the mission Jesus outlined in Luke 4:18-19, “to proclaim good news to the poor, to set the captives free, to give sight to the blind, to release the oppressed, and to announce the year of the Lord’s favor”—even under imperial oppression and hostile systems. In short, the ekklesia doesn’t cower before death’s systems, but displaces death’s dominion with life, injustice with righteousness, and chaos with God’s peace. The ekklesia exists to participate in God’s future invading the present – at the very gates where death appears strongest.

Delegated Authority: A Force for Restoration, Not Domination

We must remember that in Jesus’ time, Rome enforced its political and cultural dominance on a massive scale, imposing its so-called “peace”—the famed Pax Romana—through violence, control, and oppression. Just as the Empire extended its presence, power, and culture to every corner of the known world, Jesus summons an ekklesia destined to spread the presence, power, and culture of God’s Kingdom—but with a radically different character: Not built on force and imposition, but founded on justice, mercy, and truth. Even more striking, Jesus entrusts His ekklesia with an authority that transcends the visible realm. As He declares in Matthew 16:19: “I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” This authority is not for control, manipulation, domination, but for, liberation, healing, and restoration. It’s an authority that breaks chains, opens paths, and establishes signs of the Kingdom in the midst of brokenness. The ekklesia is, therefore, the visible instrument of an invisible Kingdom—a divine force breaking forth powerfully exactly where it’s needed most.

How should we understand this authority in practical terms? Just as Rome governed through its senate and imperial structures—issuing decrees that shaped cities and nations under its rule, Jesus’ ekklesia is vested with spiritual authority delegated by the King Himself—Christ—to establish the principles and values of His Kingdom on earth. The metaphor of receiving “the keys of the Kingdom” (Matthew 16:19) signifies the authority to bind and loose—that is, to release heaven’s governance on earth, to discern His will in every circumstance, and to declare His lordship in ways that transform lives, serve communities and advance the common good. This makes the church the King’s executive body—not a passive institution, but a living, active community that that confronts the structures of evil and the powers of death in all their forms, bringing light to dark places and sowing shalom where chaos abounds. Unlike Rome’s top-down domination, the ekklesia doesn’t impose the Kingdom; it unleashes it through surrendered obedience to Christ’s reign.

Nevertheless, we must emphasize that this “authority” operates fundamentally differently from the oppressive power structures the world employs. Jesus explicitly warned His disciples against “lording it over” others as worldly rulers do (Matthew 20:25-28), but instead to learn the way of servanthood. In fact, He demonstrated through washing His disciples’ feet that Kingdom authority is exercised from the bottom up—through love, humility, and service to others. Christ-like leadership is measured by sacrificial love, not by positional authority (2 Corinthians 12:9; John 13:34-35). In other words, the ekklesia isn’t called to establish theocratic rule, control from positions of power, or impose faith through coercion. Rather, it is called to be a community that embodies an alternative way of living, thinking, and acting – one that models Christ’s servant-hearted governance and leads toward freedom, justice, and restoration.36 This vision is deeply rooted in the ancient prophecy of Isaiah: “The government will be upon His shoulders… and His peace (shalom) will have no end” (Isaiah 9:6–7). The ekklesia, then, is the living body of Christ through which God extends His upside-down Kingdom of shalom into the world.

The ekklesia is not called to impose a theocratic regime or control from positions of power, but to be a community that, by its example of life, testimony, and dedication, reveals a new way of being, thinking, and acting.

The Power of Embodied Testimony: Transformation from Below

We must clarify that this doesn’t require believers to reject opportunities to hold positions of public influence or abandon political engagement altogether. There is nothing inherently wrong with Christians—guided by genuine vocation—serving in public office or influencing legislation at local, state, or national levels in pursuit of a more humane, ethical, and just society. However, history shows us that the early ekklesia didn’t challenge the Roman Empire through senatorial debates or legislative decrees, but through grassroots faithfulness in homes, neighborhoods, and streets – by forming disciples who embodied a new way of being human. Their transformative power emerged not from political leverage, but from a radical commitment to live out a new humanity amid a world corroded by oppression, violence, and idolatry. The first disciples understood this mission clearly. That’s why they founded missional ekklesias, proclaimed the Gospel of the Kingdom, and – most importantly – incarnated its values. In doing so, they subverted imperial structures not by seizing power, but by exposing their bankruptcy through an alternative way of life. As Acts 17:6 declares, they “turned the world upside down”:

- They cared for the poor, the orphans, and the widows—breaking through the prevailing culture of indifference and elitism.

- They united Jews and Gentiles—tearing down racial and ethnic barriers and modeling a new way of living together.

- They denied the absolute supremacy of Caesar by proclaiming, “Jesus is Lord”—a subversive act in direct opposition to imperial ideology.

- They practiced nonviolence and forgiveness—countercultural responses in a society that normalized vengeance and domination.

- They created networks of solidarity that contrasted sharply with the hierarchical patronage system of the Roman world.

- They refused to serve in the Roman army, because their sole allegiance was to Christ the King.37

These weren’t merely religious practices – they constituted a comprehensive challenge to the political, economic and social order, first in Judea under the Sanhedrin and then across the Roman Empire. The persecution early believers faced wasn’t primarily about their religious beliefs – it was largely because of their alternative way of life. By proclaiming Jesus as the true Savior and King, they didn’t just question imperial authority – they exposed the empire’s moral and spiritual bankruptcy. Roman officials rightly saw these “subversive” communities as a direct threat to their power and control.38 The lesson remains vital today: While political engagement has its place, the church’s most potent transformative power flows from being the Kingdom before seeking to legislate it.

The Ekklesia Does Not Exist for Itself: Its Public Vocation

History reveals a tragic irony: The church has often undermined its mission by aligning itself with political power to impose its faith, resulting in abusive theocracies and distorted forms of Christian nationalism.39 Yet at its best, the ekklesia has been a profoundly transformative force: founding hospitals, caring for the marginalized, defending social justice, promoting education, and contributing to expanded human flourishing by encouraging the development of societies that adhere to the rule-of-law that improved access to welfare and justice for all.40

This vision of an embodied church – one that engages rather than flees from societal challenges through Christ’s love and truth – perfectly aligns with Paul’s “ambassador” metaphor (2 Corinthians 5:20). Like diplomatic envoys that represent their nation—the ekklesia has been called to represent God’s kingdom and act in defense of its values and interests (justice, mercy, truth). In other words, the ekklesia was never meant to be a self-contained religious club, a liturgical service provider, or a fortress against culture, but an active assembly advancing the interests of the Kingdom.

In conclusion, the ekklesia does not exist for itself, but for the world. A church that lives only for its own preservation and growth ultimately becomes a counter-testimony to the Gospel.41 As the German theologian and martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer once wrote, “The Church is only the Church when it exists for others… not to dominate, but to serve.”42 On a local level, this means that every community of disciples is called to embody God’s shalom precisely where it dwells—with a concrete commitment to its immediate surroundings. As missiologist and Anglican bishop Lesslie Newbigin affirmed, “It is of the very essence of the church to exist for that place, for that section of the world of which it has been made responsible.”43 This calling requires the church to immerse itself in the life of its neighborhood, district, or municipality—discerning its needs and challenges, and responding with the compassion and justice of the Kingdom. When the ekklesia truly lives for its community rather than alongside it, the Gospel stops being an abstract doctrine and becomes visible Good News.

One Body for the Whole City: Unity and Collaboration for Holistic Transformation

This calling extends beyond individual congregations. As Belgian-Brazilian historian Eduardo Hoornaert notes, early Christians didn’t speak of “the churches of Ephesus” or “the churches of Corinth,” but of the church in Ephesus or the church in Corinth – recognizing that while multiple house assemblies existed, they collectively formed one body with a shared mission for their entire city.44 Today, this spirit of unity and collaboration is just as urgent—if not more so. No congregation should operate in isolation if it truly longs to see its city transformed according to God’s Kingdom. When diverse ekklesias collaborate, they strengthen Christian witness, model reconciliation in fragmented and fractured societies, and multiply impact across all spheres of city life. As Swiss theologian Karl Barth observed: “The first congregation was a visible group, causing a visible public stir. If the Church does not have this visibility, then it is not the Church.”45 This visibility means:

- Faith moves beyond private devotion to public engagment.

- The ekklesia becomes Christ’s tangible presence in urban spaces.

- Collaborative action advances God’s Shalom citywide.

Only when the church lives as one visible body – confronting broken systems and healing communities together – will the gates of Hades truly fail against it.

Part 7: The Ekklesia — A Worshiping Community in Communion with God

Worship as the Wellspring of Identity and Mission

The early Christians understood themselves not only as a healing, discipling, and transformative community, but as people whose very purpose flowed from intimate, continual communion with God. Without this worship-centered connection to the Divine, their mission lost both meaning and power. While modern Christianity often reduces “worship” to Sunday services or liturgical rituals confined to church buildings,46 Scripture and early church practice reveal a far more profound reality: True worship meant the total offering of one’s life to the God of shalom, fueled by a desire to reflect His character and participate in His mission in the world. As theologian Marva Dawn observed: “We cannot respond to God as the object of our praise unless we first see Him, know Him, and let Him be God in our lives.”47 For these first believers, worship became the heartbeat of their countercultural community – the wellspring from which flowed their radical love for God and neighbor, their courage in persecution, and their commitment to the Missio Dei.

This communion with God was inseparable from communion with one another. The Lord’s Table stood at the center of their shared life—not merely as ritual but as revelation. Around bread and wine, they encountered both the presence of Christ and the presence of their brothers and sisters. Worship and fellowship became one reality: adoration that overflowed into love, gratitude that birthed generosity, and communion that turned outward in mission. Rather than a compartmentalized religious activity, worship permeated every aspect of their existence—informing how they lived, loved, and engaged the broken systems around them. In this way, worship did not end at the altar; it continued at the tables of everyday life, where grace was translated into hospitality, service, and justice. In our next section, we’ll examine more closely how the early church embodied this worship-centered calling.

Everyone Worships Something: From the Dehumanizing Cost of Idolatry to Worship’s Restorative Power