Introduction

Every generation of Christ-followers must grapple with a crucial question: How should we relate to the powers that shape our world? Whether we’re talking about governments, corporations, media, or religious institutions, these forces profoundly impact not only our individual lives, but also the lives of our neighbors and the fabric of society itself. For churches and ministries engaged in fragile urban contexts—seeking spiritual transformation, advocating for justice, walking with the vulnerable, and holistically discipling people—this is far from a theoretical issue. It is a deeply spiritual and practical concern that influences everything from how we serve to how we pray.

Lutheran theologian Walter Pilgrim lays out a biblically grounded framework to help us discern our role in times like these. He names three possible responses the church can take in relation to state power and cultural institutions: a critical-constructive posture when partnership is possible, a critical-transformative stance when reform is needed, and a critical-resistive approach when the powers have become oppressive or idolatrous.1

When should we collaborate? When must we confront? When are we called to submit? And when must we resist?

These models are not rigid formulas, nor are they mutually exclusive or static. Rather, they call us into ongoing, prayerful discernment, helping us ask: When should we collaborate? When must we confront? When are we called to submit? And when must we resist? Grounded in Scripture, informed by history, and attentive to the challenges of our time, this framework can guide us to wisely and faithfully navigate the political and cultural forces shaping society—so that we may bear courageous, Kingdom-centered witness in a complex and often compromised world.

#1: Critical-Constructive: Collaboration with Eyes Wide Open

The critical-constructive stance is appropriate in contexts where governing authorities claim to pursue justice, uphold constitutional order, and operate within systems of checks and balances. This posture assumes that—even though the powers are never neutral or infallible—they may still be open to implement just policies and serve the common good. Paul’s reminder in Romans 13:3-4 that “rulers hold no terror for those who do right” reflects this possibility of legitimate governance under God’s sovereign oversight.2

In this stance, the church acts as a collaborator, not in blind allegiance, but with principled support. This allows space for strategic partnership in areas such as poverty alleviation, refugee care, violence prevention, environmental stewardship, community development, economic growth and urban renewal. This is the posture many churches have adopted in democratic societies where public theology and civic engagement are valued expressions of faith. It reflects Jeremiah’s admonition to the exiles to “seek the peace (shalom) of the city… for in its peace you will find your peace” (Jeremiah 29:7).

However, this relationship requires what Pilgrim calls a “differentiated partnership.” While the powers that be will try to seduce the church, it must not be co-opted by the powers it supports. It must remain a distinctive moral community with its own prophetic voice. The well-known maxim—often attributed to political strategist Lord Palmerston, who famously said, “We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual and those interests it is our duty to follow”3—takes on deeper meaning in a theological context. For the church, this principle serves as a reminder that while strategic cooperation with governing powers may at times be appropriate, allegiance to Christ and His Kingdom must always remain supreme. The church must never become so aligned with any political entity that it loses its prophetic voice or forgets its primary vocation as a witness to the reign of God. This demands vigilance, as the church must be prepared to critique the very systems it partners with, especially when their actions deviate from justice or reinforce oppression.

This was the approach of figures like William Wilberforce, who worked within the British Parliament to abolish the slave trade, stating, “You may choose to look the other way, but you can never say again that you did not know.”4 Similarly, the civil rights leader and Baptist pastor, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., called upon the American state to live up to its founding ideals, proclaiming, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere”.5

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

– Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

#2: Critical-Transformative: Watchful Distance, Prophetic Pressure

The critical-transformative stance becomes necessary in more fragile contexts—emerging democracies, transitional governments, or nations marked by weak institutions and uneven rule of law. Here, the powers may claim commitment to the common good but often fall short in practice. They may be marred by corruption, exclusion, special interests, or apathy. Yet, change remains possible.

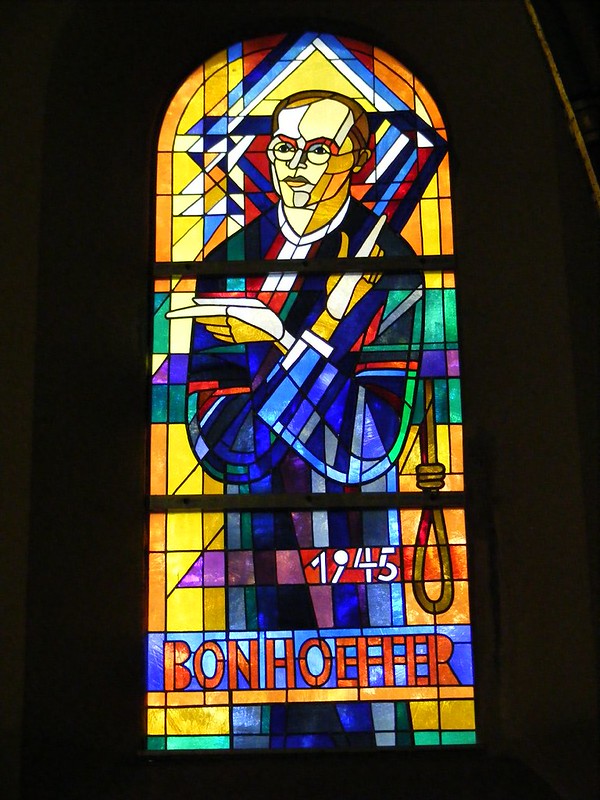

In these contexts, the church cannot function as an equal partner with the state. Instead, it takes on the role of watchdog and prophetic voice—remaining present in the public square yet maintaining a posture of critical distance. From this position, the church exposes injustice, proposes alternative possibilities, and advocates for structural change through peaceful yet courageous means. This may include nonviolent resistance, public lament, community organizing, or civil disobedience. As the prophet Isaiah warned, “Woe to those who make unjust laws, to those who issue oppressive decrees” (Isaiah 10:1). Unlike the critical-constructive stance, this posture is marked by tension and conflict, though it avoids outright antagonism whenever possible. It is a posture of uneasy peace, calling those in power to repentance and reform. The church does not retreat into sectarianism, nor does it align itself with partisan movements or allow itself to be co-opted by the state. Instead, it draws deeply from its own theological identity to bear witness to a different kind of kingdom—one not built on domination, but on justice, mercy, and humility (Micah 6:8). As the German theologian and martyr, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, reminds us, “The church is the church only when it exists for others.”6 In this spirit, the church points to another way of being human—a more excellent way, rooted not in the power structures of this world, but in the self-giving love of the crucified and risen Christ.

Biblical examples abound. Think of John the Baptist confronting Herod over his unlawful actions (Mark 6:18), Nathan confronting David with the parable of injustice (2 Samuel 12), or Amos confronting the Northern Kingdom’s economic oppression: “Let justice roll on like a river, righteousness like a never-failing stream” (Amos 5:24). These prophets did not abandon their societies, but neither did they flatter the rulers. They spoke with divine clarity, even at great personal cost.

Modern equivalents include Óscar Romero, Archbishop of El Salvador, who moved from cautious cooperation to open confrontation as he witnessed increasing state-sanctioned violence and the suffering of the poor. “When the church hears the cry of the oppressed,” he preached, “it cannot but denounce the social structures that give rise to and perpetuate the misery.”7 Similarly, the Anglican archbishop of South Africa, Desmond Tutu, became the moral conscience of his country’s struggle against apartheid, proclaiming, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.”8 His prophetic work offered both challenge and hope to a nation in turmoil.

“If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.”

– Desmond Tutu

#3: Critical-Resistive: Holy Dissent in the Face of Empire

Finally, there are times when the powers can no longer be seen as partners—or even as flawed agents of the common good—but have become perpetrators of demonic injustice, dehumanizing systems, and idolatrous ambitions. In such situations, collaboration is no longer possible. These rulers are not committed to justice but to domination, often cloaking their actions in the language of spirituality while behaving in ways that stand in direct contradiction to the fruits of the Spirit (Galatians 5:22–23). Their failures are not accidental—they are willful rejections of righteousness and deliberate resistance to godly transformation. In these contexts—under authoritarian rule, violent regimes, or structures of institutionalized idolatry—the church is called to adopt a critical-resistive posture. This does not mean rejecting all submission to earthly authority. Rather, it redefines submission as a deeper faithfulness to God over Caesar, a loyalty that places obedience to the Kingdom of God above compliance with the demands of oppressive powers.

This was precisely the situation faced by the early Christians under the Roman Empire. Their posture was shaped by the example of Jesus himself—who willingly submitted to Rome’s arbitrary and unjust judicial system yet firmly rejected its imperial theology and practices. When Paul declared, “Jesus is Lord” (Romans 10:9), he was not making a private religious confession. He was making a public, subversive political claim—directly challenging the imperial cult that revered Caesar as lord, savior, and even son of God.9 To confess Jesus as Lord was to deny Caesar’s ultimate authority and to live in loyal resistance to an empire that demanded worship and allegiance.

Similarly, John’s apocalyptic vision in the book of Revelation was not a work of detached futuristic theological speculation, but a prophetic critique of the Roman empire disguised in symbolic language. His vivid imagery of beasts, a dragon, and the infamous “Babylon the Great, mother of prostitutes and of the abominations of the earth” (Revelation 17–18) was a direct indictment of Roman imperialism—a system marked by greed, idolatry, economic exploitation, violent domination and the self-preservation of a small but extremely powerful and rich elite.

In such moments, the church is called to costly resistance and faithful allegiance to a higher authority. It must be willing to suffer for truth and righteousness. It must give shape to alternative communities of hope—ekklesiae that live by a different ethic, pledge allegiance to a different King, and embody the values of a different kingdom. These communities are grounded in worship of the one true God, the Creator and Sustainer of all things; in mutual support rooted in generosity and abundance; and in fearless witness and prophetic action. As Philippians 2 reminds us, Christ humbled himself and became obedient unto death—not to affirm the legitimacy of unjust systems, but to conquer evil through self-giving love. The cross is not only the means of our salvation; it is also the pattern for nonviolent, suffering resistance. As Dietrich Bonhoeffer powerfully wrote, “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.”10

The church in Nazi Germany faced this kind of crisis. While many capitulated to the regime—embracing the nationalist theology of the German Reichskirche—a remnant known as the Confessing Church, led by figures such as Karl Barth and Dietrich Bonhoeffer, chose a different path. Bonhoeffer famously declared, “The church must not only bind the wounds of victims beneath the wheel, but also seize the wheel itself.”11 His involvement in the resistance movement and his eventual martyrdom in the Flossenbürg concentration camp were grounded in unwavering submission to Christ alone. His life and death reveal the depth of faith and courage required when justice is trampled and the state becomes an instrument of evil.

Today, that same spirit of resistance lives on in Christian communities under authoritarian regimes—from Myanmar to Eritrea, North Korea, Somalia, and Yemen—where churches are forced underground, pastors are imprisoned, and even gathering for worship becomes an act of civil disobedience. Often hidden, persecuted, or scattered in exile, these believers continue to bear witness to the God of justice, refusing to bow before the idols of political, religious and cultural power—even at great personal cost. Their communities embody what French sociologist Jacques Ellul called “hope against hope,” bearing witness not to the triumph of empire, but to the coming reign of God (Romans 4:18).12

“The church must not only bind the wounds of victims beneath the wheel, but also seize the wheel itself.“

– Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Discerning the Times: Prophetic Wisdom in Action

These paradigms—constructive, transformative, and resistive—are not isolated strategies or rigid formulas to be applied mechanically. Rather, they serve as theological tools for ongoing discernment and contextual engagement. Each flows from a deeper spiritual posture of submission to God’s ultimate authority above all earthly powers. It is this submission that becomes the lens through which we discern how to respond to human authorities. To help guide this discernment, we can ask three essential questions:

1- Are the state powers genuinely committed to a just society?

- Do they protect the vulnerable?

- Do they uphold the rule of law and due process?

2- Who benefits and who is harmed by its policies and actions?

- Do they pursue the common good or serve a privileged elite?

- Are some communities scapegoated or excluded?

3- Are the powers open to correction—or bent on coercion, control, and censure?

- Is there space for public discourse, critique and reform?

- Or is dissent suppressed, truth manipulated, and power absolutized?

Faith communities must approach these questions prayerfully, listening attentively to both the witness of Scripture and the voices of the marginalized. They must analyze state power with a critical eye, aware that evil often hides behind a veneer of benevolence—especially when it benefits the dominant group—and cloaks itself in the language of stability, tradition, or even religion. In the face of such deception, the church must remain deeply rooted in its ecclesial identity—not as a passive observer of political realities, but as an active, courageous agent of God’s Kingdom, bearing prophetic witness to justice, truth, and love.

Conclusion: The Church as God’s Prophetic People

In the end, the church’s ultimate allegiance and deepest submission is not to any earthly empire, political party, or cultural ideology—but to the crucified and risen Lord. As followers of Jesus, we are not called to secure power, preserve comfort, maintain our own security, or align with the dominant narrative. We are called to be salt and light in the world (Matthew 5:13–14), a city on a hill, a living sign of the coming reign of God.

This kind of submission is anything but passive. It is a powerful act of defiant hope—one that frees the church to act boldly, to partner with good, to protest against evil, and to endure suffering with unwavering faith. Whether through constructive collaboration, transformative advocacy, or resistive witness, the mission of the church remains unchanged: to proclaim and embody the justice, peace, and truth of God’s Kingdom in a world still marred by injustice and idolatry—a world still groaning for redemption (Romans 8:22–23).

In an age where the lines between church and empire are increasingly blurred, where theological conviction is often traded for political expedience, and where prophetic voices are dismissed, silenced or domesticated, we must recover the courage, clarity, and compassion of the early church. We must be willing to speak truth to power, to embrace the cross-shaped path of Jesus, and to stand in solidarity with the poor, the oppressed, and the forgotten. As ambassadors of Christ (2 Corinthians 5:20), our calling is not merely to critique the powers—but to live differently, to witness faithfully, and to model a new way of being human. Grounded in Scripture, shaped by the Spirit, and committed to the way of Jesus, may we become a church that refuses to bow before the idols of security, nationalism, or comfort—and instead, boldly declares with both word and deed: “Jesus is Lord.”

In doing so, we do not simply resist the world’s broken systems. We announce the arrival of a new reality. We make visible, in real time and space, the Kingdom that cannot be shaken. And in that faithful resistance, we discover not only our truest witness—but our truest worship: “He has shown you, O mortal, what is good. And what does the Lord require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God.” (Micah 6:8)

Endnotes

- Walter Pilgrim, Uneasy Neighbors: Church and State in the New Testament (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 2000). ↩︎

- A key posture running through the New Testament is that of submission—but submission not in the sense of blind obedience or passive compliance. Rather, as theologian Walter Pilgrim explains in Uneasy Neighbors: Church and State in the New Testament, submission is a theological recognition that earthly powers exist under the sovereignty of God. It affirms the role of governments in promoting order and the common good (Romans 13:1–7; 1 Peter 2:13–17), but it never grants them absolute authority. As Pilgrim notes, submission is not the same as surrender. It is a starting posture of humility and discernment, from which the church evaluates whether to collaborate, challenge, or resist. In this sense, submission becomes the spiritual foundation for three active and biblically grounded paradigms of engagement with state and cultural powers. ↩︎

- Henry John Temple, Viscount Palmerston, speech to the House of Commons, March 1, 1848, in Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates, 3rd ser., vol. 97 (1848), col. 122. ↩︎

- William Wilberforce, quoted in Eric Metaxas, Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the Heroic Campaign to End Slavery (New York: HarperOne, 2007), 251. ↩︎

- Martin Luther King Jr., Letter from Birmingham Jail, April 16, 1963, in Why We Can’t Wait (New York: Signet Classics, 2000), 72. ↩︎

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Letters and Papers from Prison, ed. Eberhard Bethge (New York: Macmillan, 1972), 203. ↩︎

- Óscar A. Romero, The Violence of Love, ed. James R. Brockman (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2004), 200. ↩︎

- Desmond Tutu, quoted in Desmond Tutu and Mpho Tutu, Made for Goodness: And Why This Makes All the Difference (New York: HarperOne, 2010), 143. ↩︎

- From the late Roman Republic into the early Empire, Julius Caesar and Augustus laid the foundation for what would become the Roman imperial cult by assuming titles traditionally reserved for the divine. Julius Caesar was hailed in the Eastern provinces as “god manifest” (θεὸς ἐπιφανής) and “savior of human life” (σωτήρ)—titles rooted in Hellenistic traditions of ruler worship and supported by inscriptions such as those from Ephesus and Ceos. These accolades, granted even before his formal deification in 42 BCE as Divus Iulius, established Caesar’s divine status both regionally and eventually within Roman state religion. Augustus, Caesar’s adopted son, solidified this divine lineage by publicly embracing the title divi filius (“son of the divine”)—a status widely proclaimed on coinage and monuments. Additionally, he was celebrated as savior (σωτήρ) in inscriptions such as the famous Priene Calendar, which referred to his birth as the beginning of “good news” (εὐαγγέλιον) for the world. While Augustus avoided the Latin title dominus (lord) within Rome due to its monarchical overtones, the Greek equivalent kyrios was widely used in the Eastern provinces, as seen in the inscription on the Mazeus-Mithridates Gate in Ephesus, which proclaimed him “lord and savior of the world.” These titles—Lord, Savior, and Son of God—not only affirmed the emperors’ supreme status but also blurred the lines between political authority and divine identity, fostering a theological-political environment that early Christians would later confront with their subversive confession: “Jesus is Lord.” ↩︎

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer, The Cost of Discipleship, trans. R. H. Fuller (New York: Macmillan, 1959), 89. ↩︎

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Ethics, ed. Eberhard Bethge, trans. Neville Horton Smith (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 134. ↩︎

- Jacques Ellul, Hope in Time of Abandonment, trans. C. Edward Hopkin (New York: Seabury Press, 1973), 7. ↩︎

Image Directory

- “Martin Luther King Jr. by Christian Rice”, Wiredforlego, Flickr, CC BY 2.0

- “Dietrich Bonhoeffer Stained Glass,St Johannes Basilikum, Berlin SW29”, Sludge G, Flickr, CC BY 2.0

- “Desmond Tutu and His Rocket Chair”, Todd Berman, Flickr, CC BY 2.0

- “Luces IV”, eskararriba, Flickr, CC BY 2.0