Introduction: Fragile Cities and Cities of Shalom

It is fascinating to consider how the Bible can be understood as a narrative tracing the development of two contrasting cities: the human city and the city of God. This tension runs like a central thread through the biblical story, beginning with the city of Babel in Genesis 11 and culminating in the New Jerusalem in Revelation 22. These cities not only serve as a powerful metaphor for understanding the overarching biblical narrative but also raise profound questions about humanity’s condition, purpose, and destiny. To delve into this theme, it is essential to first provide some key definitions that shed light on the nature of these two cities.

What Is a Fragile City?

The human city, as depicted in the Bible and evident throughout human history, is inherently fragile—a manifestation of unchecked ambition and the self-serving pursuits characteristic of human nature. At first glance, such cities may appear magnificent, boasting grand architecture, economic power, and cultural influence. They dazzle with their splendor and ostentatious displays of greatness, enticing people with a superficial charm and the illusion of opportunity for all. However, this polished exterior often conceals a much darker reality: overwhelming inequality, poverty, corruption, fragmentation, segregation, and insecurity. These cities are fundamentally ill-equipped to sustain the holistic well-being of all their inhabitants, as they are primarily designed to benefit the elite.

Even the most “successful” modern cities often harbor a hidden and grim side: marginalized neighborhoods, broken justice systems, weak public institutions, social exclusion, widespread despair, and a profound spiritual void. The absence of social cohesion, effective governance, healthy environmental conditions, and equitable economic growth perpetuates a culture of distrust, systemic violence, and corruption. A significant portion of their citizens lacks access to adequate infrastructure, consistent basic services, protection of fundamental human rights, and opportunities for advancement. Beneath the surface of their apparent grandeur lies a deep-seated fragility that is unsustainable and inevitably leads to eventual internal collapse from within. Today, the majority of the world’s 4,037 cities with populations exceeding 100,000 can be described as fragile.1

What Is a Shalom City?

In stark contrast to fragile cities, the City of God—often referred to as the City of Shalom—stands apart. It is not defined or sustained by its outward appearance but by its internal foundations: peace, justice, integrity, and the flourishing of all. This city is built not on human ambition but on divine intention, designed to restore creation and reconcile all things to their original purpose. The shalom that characterizes these cities transcends superficial peace; it embodies a holistic well-being where every aspect of life—harmonious relationships, equitable social justice, generous economies, and deep spirituality—is aligned with God’s purpose and design. (For a detailed definition of shalom, see the footnotes)2 . Cities of Shalom serve as centers of hope, development, and holistic well-being. They are defined by being livable, safe, and economically prosperous environments for all, guided by visionary and integrous leaders alongside vibrant faith communities that cultivate committed disciples seeking the common good. Moreover, a City of Shalom is marked by a strong and organized civil society driving sustainable change, ensuring no community is excluded or left behind, but all are fully integrated into the city’s broader development. These cities embody the biblical ideal of “nothing is missing, and nothing is broken,” fostering peace and prosperity for all their inhabitants. Effective governance, strong institutions, and access to justice form the foundational pillars that sustain enduring peace. In summary, Cities of Shalom are characterized by:

- Safety and Prosperity for all

- Homes, People and Faith Communities filled with Hope

- Access to good Governance, Strong Institutions, and Justice for all

- Livable, Healthy, and Sustainable Environments

- Organized, Cohesive, and Resilient Civil Society

- Marginalized Groups and Communities fully Integrated

The metaphor of these two cities, woven throughout the Bible, invites us to look beyond their physical and geographic descriptions to see them as reflections of fundamental choices and destinies for humanity. On one side, fragile cities reveal the transience and vulnerability of human works—built for self-glorification and often at the expense of others. On the other, Cities of Shalom embody God’s eternal purpose: communities grounded in His peace, justice, and wholeness, where every aspect of life reflects His design and love.

This contrast is not merely a theological illustration but an urgent call to rethink the values and priorities shaping our cities and communities. Will we follow the path of human ambition, marked by selfish pursuits of power and control that inevitably lead to collapse? Will we embrace God’s project, offering holistic and lasting well-being for all? Or, worse yet, will we abdicate our calling, neglecting our responsibility to act as agents of transformation, passively waiting for Christ’s return to fix it all? The answers to these questions will determine whether our cities reflect more of the fragility of Babel or the fullness of the New Jerusalem.

Will we embrace God’s project, offering holistic and lasting well-being for all? Or, worse yet, will we abdicate our calling, neglecting our responsibility to act as agents of transformation, passively waiting for Christ’s return to fix it all?

The Fragile City in the Bible

The fragile city makes its first appearance in the Bible with the construction of Babel and its infamous tower (Genesis 11:1-9). Babel serves as the archetype of the anti-Shalom city—a place where human elites trample on the rights and dignity of the marginalized, exploiting the masses to consolidate their own power and privilege. Babel’s ambition to “make a name for themselves” symbolizes humanity’s desire to impose control and dominance, directly opposing God’s vision of shared Shalom. It seeks to reshape people into its own image, rather than honoring their creation in the image of God.

Biblical Examples of the Fragile City

This metaphorical city reemerges in various forms throughout Scripture, each instance highlighting its role as a symbol of oppression, idolatry, and rebellion against God:

- Sodom and Gomorrah: Destroyed around 2000 B.C., these cities are among the first in the Bible, after Babel, to embody moral corruption and social injustice (Genesis 19:1-29). Located in the Jordan plain near the Dead Sea, they are condemned not only for immorality but also for oppressing the vulnerable and neglecting social justice, as noted in Ezekiel 16:49-50: they were arrogant, gluttonous, and failed to help the poor and needy. These cities stand as enduring symbols of wickedness, serving as a warning of how the absence of shalom can lead to total destruction.

- Memphis, Egypt: Representing oppressive power, Memphis symbolizes the enslavement of the Israelites for 400 years (Exodus 1:8-14). Under Pharaoh’s rule, Egypt exploited the labor and lives of the Hebrew people to sustain its imperial grandeur. Interestingly, the term “Hebrews” (ʿibrim) initially referred to marginalized groups living on the fringes of major urban societies in the ancient Near East and came to denote the poor, displaced, and landless. This period, likely in the 15th century B.C., portrays Egypt as a civilization that denies God’s shalom, perpetuating systemic injustice, exploitation, and oppression.

- Nineveh, Assyria: Renowned for its military might and cruelty, Nineveh, particularly during the 8th century B.C., epitomized the fragility of oppressive empires. Under kings like Shalmaneser V and Sennacherib, Assyria destroyed the Northern Kingdom of Israel in 722 B.C. (2 Kings 17:5-6). Known for mass deportations that uprooted conquered peoples, Nineveh left devastation and cultural fragmentation in its wake. The prophet Nahum describes Nineveh as arrogant and corrupt, a fragile city destined to fall because of its wickedness and oppression (Nahum 3:1-7).

- Babylon: As the capital of the Babylonian Empire under Nebuchadnezzar II, Babylon was renowned for its cultural and architectural grandeur, but also for its idolatry and oppression. In 586 B.C., Nebuchadnezzar conquered Jerusalem, destroyed the Temple, and exiled Judah’s elite (2 Kings 25:1-21). In Scripture, Babylon symbolizes arrogance and rebellion against God, consumed by its lust for power and moral decay (Isaiah 13:19-22; Jeremiah 50:1-3). It stands as a lasting emblem of human pride and resistance to divine authority.

- Antioch, Seleucid Empire: In the 2nd century B.C., Antioch became a symbol of cultural and spiritual oppression when the Seleucid rulers enforced Hellenization on the Jewish people. Under Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the Temple in Jerusalem was desecrated in 167 B.C., sparking the Maccabean Revolt (1 Maccabees 1:41-64). This episode highlights the fragile city as a force of military, cultural, and spiritual domination that sought to erase the Jewish peoples’ identity and faith, prompting a fight to restore religious freedom andshalom to their nation.

- Rome: The Roman Empire, with its capital in the city of Rome, became the dominant power during the centuries around Christ’s time on earth, characterized by military strength, centralized political control, and imperial oppression, including the persecution of early Christians (Acts 4:27-28; 1 Peter 5:13). Despite the façade of the Pax Romana as an era of stability and peace, this “peace” was sustained through military force, economic exploitation, suppression of conquered nations, and religious control via emperor worship. In the New Testament, Rome is portrayed as “Babylon the Great, the mother of prostitutes and of the abominations of the earth” (Revelation 17:5), aligned with the forces of evil represented by the dragon (Revelation 12:17; 13:4-8). Rome symbolizes a corrupt and oppressive system that glorified itself, seducing governors and common people with its moral decadence, luxury, and idolatry (Revelation 17:1-2). Far from promoting true well-being, it perpetuated a human order that denied the peace, justice, and wholeness that only God’s Kingdom can provide.

The Defining Characteristics of Fragile Cities

From Babel in Genesis 11 to Babylon in Revelation 17, each of these cities and the empires they represent reflect the essence of fragile cities: centers of fleeting power that captivate people with superficial allure, only to devour them once they fall into their trap. These cities strive to “make a name for themselves,” and as a result, their systems, structures, and societies are marked by the following traits:

- Religions of Control: Fragile cities are characterized by religions focused on hollow rituals, devoid of genuine devotion to God and love for others. These empty religious practices fail to transform hearts or lives and are instead wielded by religious leaders and cultural elites as instruments for control and oppression. Rather than fostering justice, mercy, and true communion with God and others, these religions sustain systems of inequality and abuse

.

- Oppressive Political Systems: Political structures in fragile cities are rooted in manipulation, injustice, and unchecked power. Deep-seated corruption ensures that governments are designed to serve the interests of a privileged few, often at the expense of the broader population. These systems maintain their grip on power through fear, intimidation, the use of military and police force, and the spread of misinformation. Justice is systematically distorted to sustain the status quo, shielding the elite and further marginalizing the most vulnerable members of society.

- Exploitative and Dehumanizing Economies: Fragile cities are marked by economies that funnel wealth and resources into the hands of a privileged few, leaving the majority in poverty or barely able to scrape by. These systems prioritize the relentless accumulation of wealth by the elite, often at the direct expense of the most vulnerable. As a result, many struggle to meet even their basic needs, while systemic inequality ensures that disadvantaged groups remain trapped in cycles of poverty and despair, with few or no opportunities to improve their circumstances.

- False and Deceitful Prophets: Fragile cities are filled with false prophets who spread lies and sustain corruption. Instead of proclaiming God’s truth and justice, these so-called “prophets” manipulate public opinion to preserve unjust structures, justify oppression, and serve their own interests. Their messages are crafted to pacify the oppressed, divert attention from systemic injustices, and solidify the power of the elite, perpetuating cycles of exploitation and control.

- Broken & Fragmented Societies: In fragile cities, the greed, selfishness, and disregard for the vulnerable modeled by their corrupt leaders—politicians, hypocritical religious authorities, and exploitative business elites—are mirrored by the people. Society becomes desensitized to human dignity, with individuals replicating the injustices they endure by exploiting those who are even weaker. This perpetuates a self-reinforcing cycle of corruption and violence, eroding the social fabric of the community and deepening systemic dysfunction.

These cities resemble the “beasts” described in the book of Daniel, rising from a chaotic sea to symbolize empires that emerge with great power but are inherently destructive and destined to fall (Daniel 7:1-8). These beasts dehumanize their inhabitants, failing to acknowledge and honor their inherent dignity as bearers of God’s image. On one hand, they objectify the masses and particularly the weak, reducing them to mere consumers, electoral votes, cheap labor, or expendable resources, trampling their worth. On the other hand, they elevate the powerful to the status of demigods, granting them a god-like role over the lives of others. Over time, these figures evolve into monstrous tyrants, exerting control over life, death, and the well-being of their people, with the marginalized and dispossessed suffering most under their rule. Tragically, this dehumanization affects both the powerful and the powerless, distorting the image of God within every person. Ultimately, Babel, in all its manifestations throughout biblical and human history, stands as the complete antithesis of God’s vision for shalom.

While Babel embodies human pride, division, dehumanization, and rebellion against God, Jerusalem reflects the divine vision of a just, complete, and harmonious society, where every aspect of life aligns with God’s purpose and design.

The City of Shalom in the Bible

In contrast, the City of Shalom traces its origins to the Garden of Eden (Genesis 2:8-15), a place of harmony where God and humanity shared deep friendship and peace. This vision of divine peace reappears briefly but significantly in Salem, the city ruled by King Melchizedek, described in Scripture as “priest of God Most High” (Genesis 14:18). The name Salem, etymologically linked to Shalom, is portrayed as a city of righteousness during the era of Sodom and Gomorrah, offering a striking contrast to the corruption of its neighboring cities. Though Salem is mentioned only briefly in Scripture, its symbolism is profound: it represents a city that embodies divine peace and righteousness in the midst of a fallen and broken world.

As the biblical narrative progresses, the City of Shalom is more fully realized with the establishment of Jerusalem (2 Samuel 5:6-10), a city recognized over the centuries as the earthly center of God’s divine presence (Shekhinah). Jerusalem, or Yerushalayim in Hebrew, combines Yeru (commonly understood as “vision” or “to see”) with shalayim, derived from Shalom (peace, harmony, justice, and holistic well-being). This etymology underscores Jerusalem as a place where God’s presence and His vision of Shalom are made tangible among His people. While often interpreted as “City of Peace,” Jerusalem’s deeper meaning could be understood as “City of God’s Vision” or “City of Divine Revelation,” where God’s redemptive plan is both revealed and realized in the lives of His people.

Jerusalem is thus often regarded as an ideal city, the earthly representation of God’s kingdom—a place where His justice, righteousness, and peace prevail (Psalm 122:6-9). It is depicted as a beacon of hope and justice, drawing nations to seek God’s wisdom and embrace a life of peace (Isaiah 2:2-4). This vision of a peaceful Jerusalem stands in stark contrast to the confusion and chaos of Babel (Genesis 11:1-9). While Babel embodies human pride, division, dehumanization, and rebellion against God, Jerusalem reflects the divine vision of a just, complete, and harmonious society, where every aspect of life aligns with God’s purpose and design.

The Characteristics of the City of Shalom

In the City of Shalom, peace is not simply the absence of conflict but the dynamic presence of justice, righteousness, and divine prosperity, permeating every human relationship and all of creation. Its defining features include perfect justice (Isaiah 9:6-7), complete reconciliation between God and humanity (Colossians 1:19-20), and harmony among all nations and peoples (Revelation 7:9-10). The City of Shalom embodies God’s heart for humanity—a society restored and transformed by His peace and justice. Its core characteristics are:

- A Religion That Fosters Connection with God, Others, and Oneself: Faith in the City of Shalom is rooted in an intimate relationship with God, encouraging inhabitants to cultivate meaningful connections not only with God but also with one another and with themselves. True worship and justice form the foundation of this city’s spiritual life, which is transformative rather than merely ritualistic. God’s peace is not merely the absence of conflict but an active presence that mends broken relationships and reaffirms the inherent dignity of every person.

- A Politics That Promotes Justice and Well-Being for All: In the City of Shalom, politics is not driven by the concentration of power among elites or the oppression of the weak. Instead, it is founded on genuine justice, prioritizing the well-being of the entire city. Power is wielded as a tool for service, not domination, and peace is actively pursued for all. The political structure of the City of Shalom is inclusive, governed by the rule of law, where even the highest authorities are held accountable. This ensures that the most vulnerable are protected and supported within a system that is fair, equitable, and committed to justice for everyone.

- An Economy That Creates Opportunities for Shared Prosperity: The economy of the City of Shalom is built to ensure that everyone has the opportunity to thrive. Unlike the exploitative systems of fragile cities, it rejects the concentration of wealth among a few at the expense of many. Instead, it promotes generosity, dignified work, equitable opportunities, and the fair distribution of public resources. By prioritizing these values, the economy of Shalom ensures that all inhabitants can live with dignity, employ their talents, be free from want, and with access to the resources they need to thrive.

- Prophets as Witnesses and Messengers of God’s Truth and Justice: In the City of Shalom, prophets are not servants of the elite, defenders of the status quo, or looking out for personal gain. Instead, they boldly challenge injustice, exploitation, and oppression, calling society to return to the principles of righteousness and mercy. In Jerusalem, prophets serve as the voice of integrity, confronting sin while offering hope for restoration and transformation. Their role is to guide the community toward God’s vision of justice and wholeness, embodying both accountability and the promise of renewal.

- A People Reflecting God’s Peace in Relationships and Conduct: The people of the City of Shalom embody God’s peace in the way they interact and live, treating everyone—including foreigners, the poor, and the marginalized— with dignity and respect. At the heart of this vision is the conviction that all humans, created in God’s image, are inherently valuable and deserve to be treated with justice. The well-being of every individual is prioritized, leaving no room for discrimination or abuse. The people of Jerusalem live by principles love, equity, and mutual care that reflect God’s peace and justice.

The Culmination of the Vision: The New Jerusalem

The ultimate realization of this vision is found in the New Jerusalem described in Revelation 21:2-4, a city descending from heaven where God will dwell with His people forever. In this city, “there will be no more death, mourning, crying, or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.” It represents the fulfillment of God’s dream for humanity—a place of eternal reconciliation, peace, and joy, where God’s shalom permeates every aspect of life: faith, governance, economics, justice, and human relationships.

This city embodies perfect justice, where human rights are upheld, opportunities for growth flourish, wealth and public resources are equitably shared, and the dignity of every individual is honored. It is the complete realization of shalom—a transformed city where heaven and earth meet. In this place, not only are human relationships restored, but creation itself is brought into harmony with God’s purpose, fulfilling His vision for a renewed world under His reign.

From its origins in the Garden of Eden, through Salem and Jerusalem, to its ultimate expression in the New Jerusalem, the City of Shalom is the biblical vision of God’s design for humanity: a place where His peace, justice, and glory permeate everything—a living, transformative reality for all who dwell there. As the antithesis of fragile cities, the City of Shalom invites us to embrace the values of the Kingdom of Heaven, offering a foretaste of the restoration, wholeness, and hope God has promised.

Bridging the Gap Between the Fragile and the City of Shalom

Throughout the Bible, we see God’s desire to build a world infused with Shalom, inviting us to participate in His divine project and collaborate in creating communities that enflesh His purpose and vision of Shalom on earth. While we currently inhabit the fragile city, we long to draw closer to the City of Shalom. But how can this be achieved? The question of how to move from the fragile city to the City of Shalom lies at the heart of the biblical narrative and is central to understanding God’s transformative mission in the world.

Israel’s Call to Live Out Shalom

According to the biblical narrative, God called an ordinary man, Abram, to leave the empire of Babel and journey to a land He would show him. God promised to bless Abram and, through him, to bless all the nations of the earth (Genesis 12:1-3). The connection between the concepts of “blessing” (barak, בָּרַךְ) and shalom (שָׁלוֹם) is significant, as both terms point to the holistic well-being that flows from God. Together, they encapsulate God’s vision of wholeness, peace, and harmony for all creation. God’s strategy for infusing the world with His shalom begins with Abram and his family. From them, God forms a people—Israel—tasked with reflecting His plans for redemption, reconciliation, and justice in the world.

From the outset, God’s intent was for His people to live by an ethic of shalom—a way of life defined by justice, well-being, and integrity in every sphere.

When Israel was enslaved by Egypt, God rescued them to establish a nation set apart for His purposes, ultimately leading to the formation of a unique and holy city: Jerusalem. From the outset, God’s intent was for His people to live by an ethic of shalom—a way of life defined by justice, well-being, and integrity in every sphere. God’s liberation of the Israelites from Egypt was not merely to create a liturgical community but to shape them into a nation with a far greater mission: to be a living testimony of His shalom to the world. Through their communal life, marked by justice, mercy, and peace, Israel was to serve as a beacon to all nations, demonstrating what it means to live in alignment with God’s kingdom and His shalom here on earth.

- Exodus 19:5-6: God calls Israel to be a “kingdom of priests and a holy nation,” defining their identity and mission as a people uniquely set apart to reflect His purposes for humanity. By referring to them as priests, God designates Israel as intermediaries between Himself and the nations—a bridge between heaven and earth. Their role goes beyond worship and service to God; they are tasked with revealing His character, shalom, and justice to the world.

- Deuteronomy 4:5-8: This passage highlights how Israel’s obedience to God’s decrees and ordinances in the promised land was intended to display their wisdom and understanding to surrounding nations. Observing Israel’s just and impartial laws and the closeness of God to His people, these nations would declare, “What a wise and understanding people this great nation is!… And what other great nation has decrees and ordinances as just and fair as this set of laws I am giving you today?” Israel’s purpose is underscored as a living example of God’s justice and wisdom, demonstrating how a nation guided by divine shalom can inspire others toward righteousness and flourishing.

- Isaiah 42:6-7: God further calls Israel to serve as an instrument of His justice and restoration, commissioning them to “open the eyes of the blind” and “free captives from prison.” This mission extends beyond spiritual renewal, signifying holistic transformation that impacts every aspect of human life. Israel was to embody God’s shalom, bringing hope, freedom, and renewal at both individual and communal levels, serving as agents of healing and reconciliation in a broken world.

- Isaiah 49:6: God expands Israel’s mission by calling them to be a “light to the nations,” emphasizing their role as bearers of His salvation to the ends of the earth. This calling is not merely a privilege but a profound responsibility—to live not for their own benefit but as guides and witnesses to the nations, revealing God’s truth, justice, and shalom through their communal life and covenantal faithfulness.

Together, these passages reveal that from Israel’s liberation in Egypt to the prophetic vision in Isaiah, God commissioned His people to serve as active agents of His shalom in the world. They were called to be a “kingdom of priests” and a “light to the nations,” embodying justice, peace, and holistic liberation while advancing God’s transformative mission on earth. God’s desire was for them to be a faithful witness through which fragile communities and cities might be transformed into places and peoples firmly rooted in shalom.

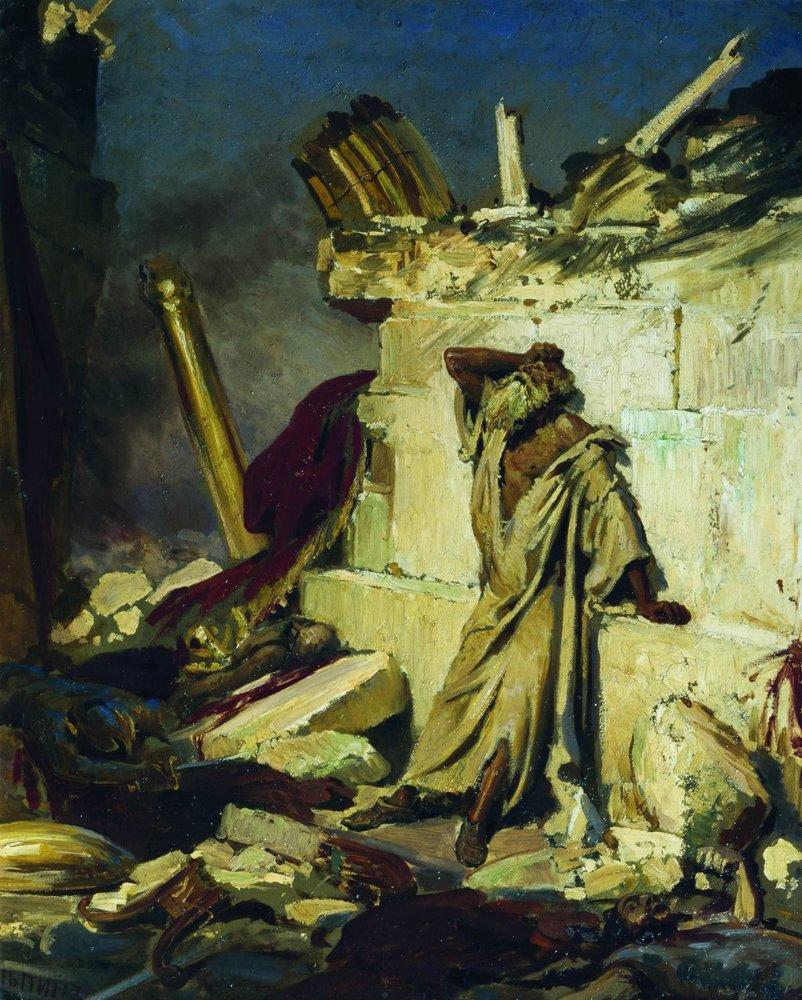

Failure and Exile

Despite their divine calling, Israel consistently struggled to fulfill its purpose throughout history. Despite clear instructions from God, Jerusalem failed to embody its mission as a beacon of justice, peace, and holiness. Instead, it became a city characterized by injustice, violence, and corruption. Ezekiel 22 describes it as a “bloody city,” where innocent blood was shed, extortion was rampant, and the most vulnerable were neglected. The prophets strongly condemned this ethical decline. Isaiah lamented that Jerusalem had become a “prostitute city” (Isaiah 1:21-23), where justice had been supplanted by murder and corruption. Jeremiah denounced its idolatry and false religiosity, warning that empty sacrifices and superficial worship could never replace obedience to justice and care for the oppressed (Jeremiah 7:3-6). Similarly, Isaiah 58 exposed the hypocrisy of a people who sought God through rituals while neglecting to free the oppressed, feed the hungry, and clothe the naked. At its core, Jerusalem failed to uphold the principles of God’s shalom—justice, compassion, and righteousness—which ultimately led to judgment and exile. Jeremiah pleaded with the city to repent, urging change before it was too late (Jeremiah 5:1-5).

Tragically, Jerusalem ignored these warnings, resulting in its invasion by the Babylonian Empire in 586 B.C. Many of its leaders and citizens were taken into exile in Babylon. The fall of Jerusalem and the subsequent exile marked one of the most devastating chapters in Israel’s history. Yet, this period of exile—lasting until around 538 B.C., when the first group returned to Jerusalem, and culminating in the reconstruction of the Temple in 516 B.C., seventy years after its destruction—did not mark the end of God’s call for His people to embody His mission. Even in exile, living in the land of their enemies, the exiled Israelites were still called to live according to God’s shalom, demonstrating His justice and peace, even amid a culture far removed from Yahweh.

Jeremiah’s Pastoral Letter

In this context, the prophet Jeremiah offers crucial guidance to the exiles. Unlike false prophets who promised a quick return to Jerusalem, Jeremiah presents a deeper and more challenging perspective in Jeremiah 29:4-7. Writing to the exiles in Babylon around 570 B.C., he urges them not to withdraw or isolate themselves from the city where they now live. Instead, he commands them to “seek the shalom of the city to which I have carried you into exile. Pray to the LORD for it, because if it prospers, you too will prosper.” This profound and paradoxical directive carries a striking irony: the people of God, who failed to reflect His shalom in Jerusalem, are now given a new opportunity to live out their calling—in the heart of Babylon, the very empire responsible for Jerusalem’s downfall. The enemy city now becomes the place where they are called to seek and promote shalom.

Jeremiah’s message is radical. Even in Babylon, the ultimate symbol of an anti-shalom city, God’s people are commanded to pursue its shalom. This call does not involve retreating from the world but engaging with it, transforming it through God’s presence, peace and justice. What seemed like punishment—their exile—ironically becomes an opportunity to fulfill God’s mission in an unexpected and challenging context. Babylon, the epitome of a fragile and fallen city, becomes the testing ground for God’s vision of shalom. This call not only redefines the exiles’ understanding of their situation but also pushes them to embody God’s mission in deeper and more transformative ways. Jeremiah’s message demonstrates that God’s shalom transcends geographic and political boundaries, reaffirming that His mission is not confined to Jerusalem or any specific place. Instead, it is a call to bring His peace, justice, and restoration even to the most unlikely and hostile environments.

The Example of Jesus

The mission to transform the world with God’s shalom is fully embodied in the teachings and actions of Jesus. In John 17:15-18, Jesus prays for His disciples, saying, “My prayer is not that you take them out of the world, but that you protect them from the evil one… As you sent me into the world, I have sent them into the world.” These words highlight that while His followers are not aligned with the world’s values or priorities, they are still sent into it with a transformative purpose: to manifest the Kingdom of God on earth.

Jesus reinforces this mission in the Lord’s Prayer, teaching His disciples to pray, “Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven” (Matthew 6:10). This prayer is not a call to withdraw from the world but an invitation to actively engage in it, bringing God’s justice, peace, and restoration into every sphere of human life. The Kingdom of God is not only a future hope but a present reality to be lived and demonstrated. Jesus calls His followers to reflect this heavenly reality in their relationships, communities, and social structures. The Kingdom of God, as envisioned by Jesus, restores humanity to its original purpose, returning people to their true identity as God’s image bearers. This vision starkly contrasts with the kingdoms described in Daniel 7—beastly systems that dehumanize and exploit, reducing people to tools for perpetuating oppression and power. By contrast, the Kingdom of God liberates, restores, and transforms, inviting people to live in wholeness, justice, and love. For this reason, Jesus teaches, “Seek first the Kingdom of God” (Matthew 6:33), for when we do so, we connect with the source of true humanity and are reconciled with God’s divine purpose for this world.

The Kingdom of God is not only a future reality; it is a present mission.

This calling involves embodying the values of the City of Shalom—justice, mercy, humility, and compassion—within the broken structures of the fragile city. Jesus modeled this approach throughout His ministry: restoring the marginalized, challenging religious hypocrisy, confronting injustice, and proclaiming hope and redemption. He did not merely teach the gospel; He lived it, showing how individuals and communities can act as agents of transformation, reflecting the Kingdom of God on earth.

The mission of Jesus’ followers is not simply to proclaim the Kingdom with words but to live it in tangible ways—through daily interactions, decisions, and relationships. This mission requires active engagement in bringing God’s restoration and peace to a world desperately in need of redemption. But how can this mission be fulfilled? What is the primary means by which fragile cities can be transformed into Cities of Shalom?

The Mission of the Ekklesia

The pursuit of transforming fragile places into communities rooted in shalom can take many forms: fostering innovative businesses, promoting socially responsible enterprises, supporting nonprofits and NGOs, advancing social movements, and advocating for human rights. However, a careful reading of Scripture reveals that God’s primary vehicle for this transformation is the ekklesia. The critical question, then, is: what kind of ekklesia does the Bible envision?

Interestingly, the term ekklesia, originating in ancient Greece, referred to a civic In the Greek and Roman urban context, this assembly met regularly to guide the development, prosperity, and future of the city-state (polis). This system of civic participation, essentially an early form of democracy or self-governance, was unparalleled in other civilizations of Asia, Africa, and Europe.3 In Jesus’ time, ekklesia carried no religious connotations; it had been firmly embedded in the political framework and vocabulary of the Greek world as a civic institution dedicated to the well-being and governance of the city for centuries.4 The assembly responsible for the welfare of the city, deliberating on matters of governance and public welfare.

It’s profoundly significant that Jesus and the apostles chose this term, rather than “temple” or “synagogue,” to describe the new community they were forming. This deliberate choice underscores their intention to create not merely a liturgical and religious gathering, but an active, missional assembly of disciples engaged in seeking the wellbeing of their environment. The ekklesia they envisioned was as a community infused with the DNA of God’s Kingdom, set apart to disciple the nations and seek the shalom of their cities.5

The Purpose of the Ekklesia

In this sense, the ekklesia is far more than a place of worship or spiritual edification; it is a community sent into the world to actively participate in God’s mission. Its calling is to transform its city by confronting the forces of evil and working toward God’s shalom. This means taking collective responsibility for guiding its surrounding context toward a better future—much like the citizens of a polis in ancient Greece who shaped the life of their city. The central purpose of the ekklesia, then, is to be a missional and active community, called by God to embody ethical and spiritual values while engaging deeply in the realities of the world. Its mission is to promote renewal and work for peace, justice, and holistic well-being. This task is aligned with God’s broader purpose—the Missio Dei—which seeks the reconciliation and restoration of all things in Christ, as declared in Colossians 1:19–20: “For God was pleased to have all his fullness dwell in him, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven, by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross.”

Jesus’ declaration in Matthew 16:18—“I will build my Ekklesia, and the gates of Hades will not prevail against it”—reveals that the mission of the ekklesia is neither passive nor defensive, but active and transformative. When Jesus speaks of the “gates of Hades,” He is referring not only to spiritual forces of evil but also to the earthly structures of power, corruption, and injustice that oppress humanity. As a community of the Kingdom, the ekklesia is called to confront these forces and serve as an agent of holistic transformation—living out a theology of restoration that dismantles systems of oppression and establishes God’s shalom on earth. The transformation the ekklesia is called to pursue touches every dimension of life:

- Spiritual, restoring relationship with God.

- Social, promoting justice and human dignity.

- Cultural, reshaping collective narratives with Kingdom values.

- Economic, fostering equity and sustainable opportunities.

- Political, challenging oppressive systems and promoting just governance.

The ekklesia, in other words, is not meant to be an inward-focused institution, but a dynamic, outward-oriented assembly tasked with infusing fragile cities with the values of God’s Kingdom. Its mission is to spread joy, hope, justice, purpose, wholeness, righteousness, ethics, belonging, and beauty—ensuring that every person experiences God’s shalom in their daily life. It should be a community where God’s people gather not only to pray and worship but to actively seek and work for the peace and well-being of their city, embodying the principles of the Kingdom both collectively and individually. In short, the ekklesia is far more than a group that gathers to worship in a building; it is a living, missional body operating 24/7 as a transformative presence in their context called to positively impact its surroundings and saturate them with God’s shalom.

Today, many traditional churches operate primarily as liturgical communities, centered on Sunday worship and teaching. However, God’s invitation goes further: to become living, missional ekklesias—not only celebrating the faith but embodying it within their context. This means becoming communities committed to making disciples and actively working for the shalom of their neighborhoods and cities. This calling is especially urgent in the Latin American context, where many cities and urban centers are marked by fragmentation, violence, injustice, and deep spiritual need. As the ekklesia embraces its mission, it can become a beacon of hope, justice, and renewal—reflecting the Kingdom of God and its transformative power in the world.

Footnotes

- Brilliant Maps, “All 4,037 Cities in the World with at Least 100,000 People,” Brilliant Maps, accessed May 28, 2025, https://brilliantmaps.com/4037-100000-person-cities/.

In essence, urban fragility is multidimensional and can be characterized by:

1. Rapid and unregulated urban growth.

2. High levels of inequality and poverty.

3. Inadequate infrastructure and weak institutions.

4. A weak civil society, lack of civic engagement, and low levels of social cohesion and trust.

5. Deeply rooted hopelessness and skepticism among the population.

6. Unhealthy environmental conditions, lack of public spaces, and vulnerability to natural disasters.

7. Insufficient economic growth and lack of employment opportunities.

8. Distrust and broken relationships at all levels.

9. Widespread violence and insecurity, both within and outside the home.

10. Ineffective governance, structural exclusion, systemic injustice, and rampant corruption. ↩︎ - Shalom is a theologically rich concept in the Hebrew Bible, often translated as “peace,” though its meaning extends far beyond that. It encompasses wholeness, completeness, prosperity, justice, spiritual contentment, well-being, and harmony. It is not merely the absence of conflict or distress, but the presence of positive and harmonious relationships—among individuals, within communities, between nations, and between humanity, the created order, and God. Theologically, shalom is central to the biblical vision of justice, righteousness, and holistic flourishing for all creation. It is intrinsically connected to the character of God and the messianic promise, where justice and peace prevail throughout the earth. In Christian theology, the meaning of shalom is further deepened through the life and teachings of Jesus Christ, who embodies and proclaims God’s ideal for a restored world, inviting his followers to actively participate in the work of God’s Kingdom: the reconciliation and restoration of all things according to His original purpose. ↩︎

- Diarmaid MacCulloch, Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (New York: Penguin Publishing Group, 2011), 28–29, Kindle edition. *Only about one-fifth of adult residents in democratic classical Athens could be described as active citizens: those considered best suited to represent the community of the polis (city). Moreover, only male citizens over the age of thirty had a voice in policymaking during the meetings of the ekklesia. However, despite these limitations, a significant number of ordinary people—who were not privileged by birth or divine favor—were held responsible for their own future and for the future of their community and city. ↩︎

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid. Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years. New York: Penguin Publishing Group, 2011. Kindle edition. ↩︎

- Silvoso, Ed. Ekklesia: Rediscovering God’s Instrument for Global Transformation. Shippensburg, PA: Destiny Image Publishers, 2017. ↩︎

Image Directory

- “Homeless tents under the Pontchartrain Expressway, New Orleans, 25 October 2021”, Infrogmation of New Orleans, CC Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

- “Senagajima near Naha, Okinawa”, Simon_photos – Getty Images.

- “Ruins of Babylon, Iraq”, Public Domain.

- “Roman collared slaves – Ashmolean Museum”, Jun, CC Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic

- “The Garden of Eden”, Frederik Bouttats, Public Domain.

- “Book of Nehemiah Chapter 6-2″ (Bible Illustrations by Sweet Media), Jim Padgett, CC Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

- “Abraham Worshiping the Three Angels” Luca Giordano, Public Domain.

- “Cry of prophet Jeremiah on the Ruins of Jerusalem“, Repin, Dominio Público.

- “Belfast St George’s Church Chancel Painting by Alexander Gibbs Miracles of Our Lord”, Andreas F. Borchert, CC Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

- “Folio 14v of the Rabula Gospels,” Public Domain.